Bridgeland Stability Conditions

In classical algebraic geometry, the study of varieties often centers on their geometric aspects, such as analyzing embedded curves, hyperplane sections, etc. A different, more algebraic perspective, however, explores these varieties through their derived categories of coherent sheaves. This categorical approach has become increasingly popular among researchers in recent years.

In a triangulated category $\mathcal{D}$, such as the derived category of coherent sheaves on a variety, the classification of objects can be highly intricate and challenging. Bridgeland stability conditions offer a framework to sort these objects into stable and semistable parts using numerical invariants. This concept comes with several appealing features, such as:

- A key feature is that the set of stability conditions, $\operatorname{Stab}(\mathcal{D})$, forms a finite-dimensional complex manifold.

- A chosen stability condition identifies classes of stable objects, for which well-behaved moduli spaces can potentially be constructed.

- The space of stability conditions, $\operatorname{Stab}(\mathcal{D})$, provides geometric tools to help understand $t$-structures on $\mathcal{D}$.

- Moreover, $\operatorname{Stab}(\mathcal{D})$ has the structure of a complex manifold, on which the group $\operatorname{Aut}(\mathcal{D})$ acts naturally.

As a result, Bridgeland stability conditions have become a powerful tool for studying the geometry of moduli spaces and related topics across various mathematical disciplines, including algebraic geometry, representation theory, and mathematical physics. They have also become central to modern homological algebra, creating new connections between these fields.

Before we dive into actual stability conditions, let’s review some basic notions of stability in the case of coherent sheaves or vector bundles. Let $X$ be a smooth projective curve. In this case, the coherent sheaves are somewhat easy to describe.

Some of the statements here will hold generally for compact Kähler manifolds so I’ll try to be explicit when this is the case. If $\mathcal{E} \to X$ is now a coherent sheaf, then one can consider two numerical invariants of $\mathcal{E}$: the rank $\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E})$, and the degree $\deg(\mathcal{E})$. We define the slope to be the quotient

\[\mu(\mathcal{E}) = \frac{\deg(\mathcal{E})}{\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E})}.\]When $\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E}) = 0$, i.e. for torsion sheaves, one sets $\mu(\mathcal{E}) = +\infty$. A coherent sheaf $\mathcal{E} \in \mathbf{Coh}(X)$ is called $\mu$-stable if $\mathcal{E}$ is torsion-free and for all proper subsheaves $0 \ne \mathcal{F} \subset \mathcal{E}$ we have

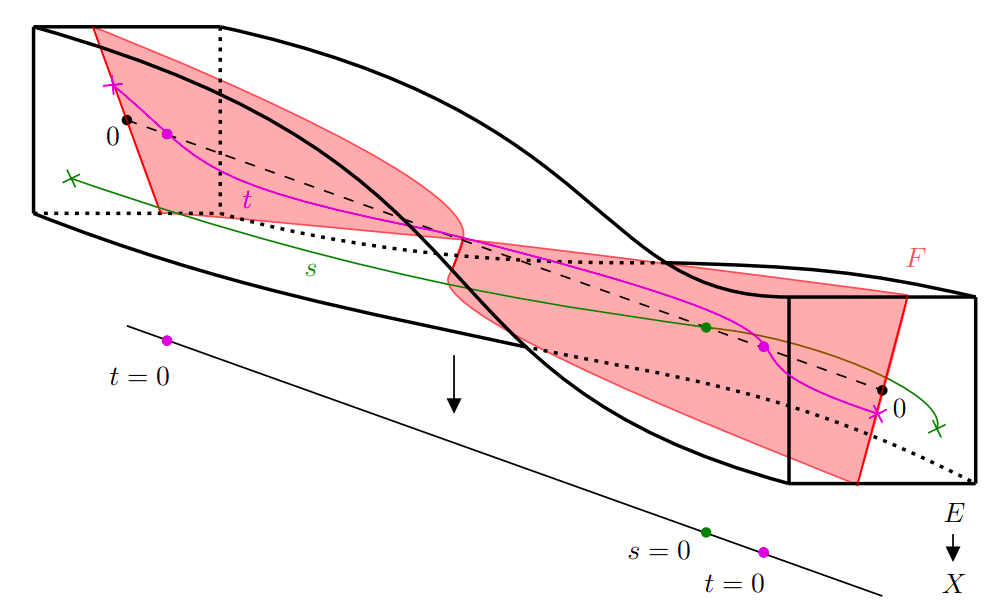

\[\mu(\mathcal{F}) \le \mu(\mathcal{E}).\]This can be intuitively understood when $\mathcal{E}$ is a holomorphic vector bundle $E$. In a sense, it’s a topological condition asking that $E$ doesn’t contain any subbundles inside it which are more twisted than $E$ after appropriate normalization by ranks. The following picture from JB McCarthy’s wonderful PhD thesis illustrates an unstable bundle $E$ having a holomorphic subbundle $F$ more twisted than $E$.

Recall that this limits the complexity of the geometry of $E$ by quite a bit. In particular, it imposes strong limitations on the symmetries of $E$, which creates a relation between stability and moduli problems.

- If $\mu(\mathcal{E}) > \mu(\mathcal{F})$, we have $\operatorname{Hom}(\mathcal{E}, \mathcal{F}) = 0$.

- If $\mu(\mathcal{E}) = \mu(\mathcal{F})$ and if $\mathcal{E}$ is $\mu$-stable, we have $$ \operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E}) = \operatorname{rk}(\operatorname{Im}(f)), $$ and $f$ is injective unless $f = 0$.

- If $\mu(\mathcal{E}) = \mu(\mathcal{F})$ and if $\mathcal{F}$ is $\mu$-stable, we have $$ \operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{F}) = \operatorname{rk}(\operatorname{Im}(f)), $$ and $f$ is generically surjective unless $f = 0$.

- Suppose that $f$ is non-zero and consider $\mathcal{E} \longrightarrow \operatorname{Im}(f) \longrightarrow \mathcal{F}$. Since $\mathcal{E}$ and $\mathcal{F}$ are $\mu$-semistable, we obtain a contradiction from $$ \mu(\mathcal{E}) \le \mu(\operatorname{Im}(f)) \le \mu(\mathcal{F}) \le \mu(\mathcal{E}). $$

- Suppose that $f$ is non-zero and that $\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E}) > \operatorname{rk}(\operatorname{Im}(f))$. Then since $\mathcal{E}$ is $\mu$-stable we obtain $$ \mu(\operatorname{Im}(f)) \le \mu(\mathcal{F}) = \mu(\mathcal{E}) < \mu(\operatorname{Im}(f)), $$ which is again impossible.

- As $\mathcal{F}$ is $\mu$-stable, if $\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{F}) > \operatorname{rk}(\operatorname{Im}(f))$, then $$ \mu(\operatorname{Im}(f)) < \mu(\mathcal{F}) = \mu(\mathcal{E}) \le \mu(\operatorname{Im}(f)), $$ which is again impossible.

The see-saw property follows from noting that rank and degree are additive over short exact sequences, but since this is a good place to introduce the stability function

\[\begin{align*} Z : \textbf{Coh}(X) \setminus \{0\} &\to \Bbb H \cup \Bbb R_{< 0} \\ \mathcal{E} &\mapsto - \deg(\mathcal{E}) + i\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E}), \end{align*}\]we’ll do just that. The ordering of the slopes is now equivalent to the ordering of the complex numbers $Z(\mathcal{G}) = Z(\mathcal{F}) + Z(\mathcal{H})$ by their arguments. The two cases correspond to the two orientations of the parallelogram formed by $0,Z(\mathcal{F}),Z(\mathcal{G})$ and $Z(\mathcal{H})$.

Note that since $Z$ is additive due to the rank and degree being additive, it factors through the Grothendieck group $K_0(X) = K_0(\textbf{Coh}(X))$, i.e.

\[Z : \textbf{Coh}(X) \to K_0(X) \to \Bbb C.\]For a sheaf $\mathcal{E}$, the stability function also determines a phase $\phi(\mathcal{E}) \in (0,1]$ uniquely by the condition

\[Z(\mathcal{E}) \in \exp(i\pi\phi(\mathcal{E})) \cdot \Bbb R_{> 0}.\]Note that $\phi(\mathcal{E}) = \arg(Z(\mathcal{E}))/\pi$ in $(0,1]$.

A worthy remark here is that if we don’t assume $\mathcal{E}$ to be locally free, then $\phi(\mathcal{F}) < \phi(\mathcal{E})$ is equivalent to $\mathcal{E}$ being $\mu$-stable or $\mathcal{E} \cong k(x)$ for some closed point $x \in X$. The weaker form $\phi(\mathcal{F}) < \phi(\mathcal{E})$ is equivalent to $\mathcal{E}$ being either $\mu$-semistable or a torsion sheaf. To circumvent the problem with torsion sheaves, we defined $\mu(\mathcal{F}) = +\infty$. However, this definition inherently treats torsion sheaves and torsion-free sheaves differently, creating a somewhat disjointed framework. Later on, when dealing with derived categories and more sophisticated notions of stability, we desire a more unified approach that can handle all objects on an equal footing. We achieve this using phases instead of the slope. By using the phase $\phi$, we can define stability conditions that are applicable to all coherent sheaves, whether they are torsion or torsion-free. For torsion-free sheaves $Z(\mathcal{E})$ lie in the upper half-plane $\Bbb H$ and for torsion sheaves $Z(\mathcal{E}) = -\deg(\mathcal{E}) \le 0$ and so $\arg(Z(\mathcal{E})) = \pi$ giving $\phi(\mathcal{E}) = 1$.

Later on, we will see that a stability condition on a triangulated category is obtained by abstracting some generalized Harder-Narasimhan filtration. Prior to that, let’s quickly recall the classical Harder-Narasimhan filtration.

This gives us a way to “approximate” a coherent sheaf with $\mu$-semistable ones. To see an example of this kind of phenomenon, recall the following classical result of Grothendieck:

If $E$ is now a vector bundle over $\Bbb P^1$, then the above theorem gives a decomposition

\[E \cong \mathcal{O}(a_1)^{\oplus r_1} \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathcal{O}(a_n)^{\oplus r_n}\]such that $a_1 > \cdots > a_n$. For $1 \le i \le n$, let

\[E_i \cong \mathcal{O}(a_1)^{\oplus r_1} \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathcal{O}(a_n)^{\oplus r_i}.\]Then we have a filtration

\[0 \subset E_1 \subset \cdots \subset E_{n-1} \subset E_n\]such that $E_i/E_{i-1} \cong \mathcal{O}(a_i)^{\oplus r_i}$. Now note that $\mu(\mathcal{O}(a_i)) = \deg(\mathcal{O}(a_i)) = a_i$ and so

\[\mu(E_i/E_{i-1}) = a_i.\]The quotients $E_i/E_{i-1}$ are $\mu$-semistable as the direct sums of $\mu$-semistable bundles with the same slope are $\mu$-semistable.

One can now consider for $\phi \in (0,1]$ the following full linear subcategory of $\textbf{Coh}(X)$:

\[\mathcal{P}(\phi) := \{ \mathcal{E} \in \textbf{Coh}(X) \mid \mathcal{E} \text{ is semistable with phase } \phi \}.\]We now recover the full subcategory of torsion sheaves for example by considering $\mathcal{P}(1)$. This will also be generalized later when we discuss Bridgeland stability conditions on triangulated categories. In the broader context of derived categories and triangulated categories, $\mathcal{P}(\phi)$ becomes a part of a slicing of the category. This is a collection of full additive subcategories indexed by real numbers (the phases) that satisfy certain axioms.

We’ll now consider stability on abelian categories. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be an abelian category and denote by $K_0(\mathcal{A})$ the Grothendieck group of $\mathcal{A}$.

Given such a stability function, we define the generalized slope of $E$ by

\[\mu_Z(E) := -\frac{\Re(Z(E))}{\Im(Z(E))}.\]The canonical example is when $X$ is a smooth projective curve, $\mathcal{A} = \textbf{Coh}(X)$ and we consider the stability function

\[\begin{align*} Z : K_0(X) &\to \Bbb C \\ E &\mapsto -\deg(E) + i\operatorname{rk}(E). \end{align*}\]A non-example is given in E. Macrì and B. Schmidt, “Lectures on Bridgeland Stability.” as follows: Let $X$ be a smooth projective variety of dimension $n \ge 2$, $\omega \in N^1(X) := \mathrm{NS}(X)_\Bbb R$ an ample divisor class and $B \in N^1(X)$. Let $\mathcal{A} = \textbf{Coh}(X)$. Then

\[\begin{align*} \overline{Z}_{\omega,B} : K_0(X) &\to \Bbb Z \\ E &\mapsto -\omega^{n-1} \cdot \operatorname{ch}^B_1(E) + i\omega^n \cdot \operatorname{ch}^B_0(E) \end{align*}\]is not a stability function on $\mathcal{A}$. For any torsion sheaf $T$ supported in codimension $\ge 2$, $\overline{Z}_{\omega,B}(T) = 0$. Here $\operatorname{ch}^B_1$ and $\operatorname{ch}^B_0$ are the twisted Chern characters given by

\[\operatorname{ch}^B_0 = \operatorname{rk}, \text{ and } \operatorname{ch}^B_1 = \operatorname{ch}_1 - B \cdot \operatorname{ch}_0.\]Since $T$ is torsion, $\operatorname{ch}^B_0(T) = 0$ and as it is supported in codimension $2$ or higher, $\operatorname{ch}_1(T) = 0$ also so $\operatorname{ch}^B_1(T) = 0$.

A remedy for this is to consider the category

\[\mathcal{A} = \textbf{Coh}(X)_{n,n-1}(X) := \textbf{Coh}(X)/\textbf{Coh}(X)_{\le n-2}\]of coherent sheaves modulo the Serre1 subcategory $\textbf{Coh}(X)_{\le n-2}$ of coherent sheaves supported in dimension less than or equal to $n-2$. Since $Z$ is additive over short exact sequences and $\mu_Z$ satisfies the see-saw property we have:

Using this we obtain the analogue of Schur’s lemma:

- $Z$ is a stability function.

- Any non-zero $E \in \mathcal{A}$ has a filtration, called the Harder-Narasimhan filtration, $$ 0 = E_0 \subset E_1 \subset \cdots \subset E_{n-1} \subset E_n = E $$ of objects $E_i \in \mathcal{A}$ such that $A_i = E_i/E_{i-1}$ is semistable for all $i = 1,\dots,n$ and $\mu_Z(A_1) > \cdots > \mu_Z(A_n)$.

Now the Harder-Narasimhan filtrations are unique up to isomorphism if they exist, but for this to be the case, some assumptions are needed on $\mathcal{A}$.

Replace ascending chains by descending chains and the category is called Artinian. As an example2, the category of representations of a quiver if of finite length, hence Noetherian as well as Artinian. The category of coherent sheaves on a variety is Noetherian, but the category of quasi-coherent sheaves on a variety is not.

The proof of the lemma above is obtained by inducting on the generalized rank. The reason we wanted this is that now we obtain

As an example, suppose that $A$ is a finite-dimensional algebra over $\Bbb C$ and $\mathcal{A} = \textbf{Mod}_A$ the category of finite-dimensional right $A$-modules. Denote the simple modules by $S_1,\dots,S_m$ and pick $Z_i \in \Bbb C$ for $i = 1,\dots,m$, where $\Im(Z_i) \ge 0$ and if $\Im(Z_i) = 0$, then $\Re(Z_i) < 0$. The Grothendieck group $K_0(\mathcal{A})$ is generated by the classes of these simple modules. Specifically, for any $A$-module $M$, its class in $K_0(\mathcal{A})$ can be expressed as

\[[M] = \sum_{i=1}^m n_i(M)[S_i],\]where $n_i(M)$ are the multiplicities of $S_i$ in a composition series of $M$. We can now define a unique homomorphism $Z : K_0(\mathcal{A}) \to \Bbb C$ by

\[Z([M]) = \sum_{i=1}^n n_iZ_i,\]where $Z_i = Z(S_i)$. This gives a stability function on $\mathcal{A}$ and since $\textbf{Mod}_A$ is a finite-length abelian category, every object $E$ has only finitely many subobjects. The set of slopes $\mu_Z(F)$ for subobjects $F \subset E$ is thus finite. We can construct a Harder-Narasimhan filtration of $E$ by letting $\mu_{\text{max}} = {\mu_Z(F) \mid 0 \ne F \subset E}$, choosing a subobject $E_1 \subset E$ with $\mu_Z(E_1) = \mu_{\text{max}}$ and repeating this for $E/E_1$ et cetera.

Here are the bad news. Up to this point, we’ve only considered smooth projective curves, what about when $X$ is of higher dimension – say a smooth projective surface? The unfortunate thing is that the category $\textbf{Coh}(X)$ does not have any natural stability conditions in the sense that the stability function factors through the Chern character $\operatorname{ch} : K_0(\mathcal{A}) \to H^\ast(X,\Bbb C)$. In the case of curves, the stability function $Z(\mathcal{E}) = -\deg(\mathcal{E}) + i\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E})$ clearly factors through the Chern character since both the degree and the rank are components of the Chern character in dimension one.

The idea Bridgeland proposed is o consider different abelian categories given by the hearts of bounded $t$-structures $\mathcal{A} \in D^b(\textbf{Coh}(X))$, and look for stability conditions on $\mathcal{A}$. Turns out that varying $\mathcal{A}$ inside $D^b(\textbf{Coh}(X))$ we get many stability conditions and obtain the structure of a complex manifold for the resulting stability conditions.

We’re finally ready to consider stability on triangulated categories and define Bridgeland stability. Let’s first redefine the notion of the Grothendieck group in the triangulated setting. Given a triangulated category $\mathcal{D}$, we define the Grothendieck group of $\mathcal{D}$ to be the quotient of the free abelian group on objects of $\mathcal{D}$ modulo the subgroup generated by the relations $[B] = [A] + [C]$ for exact triangles $A \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow C \longrightarrow A[1]$.

There are two ways to define a stability condition on a triangulated category $\mathcal{D}$. One is to consider a bounded $t$-structure $\mathcal{A} \subset \mathcal{D}$ together with a stability condition $Z : K(\mathcal{A}) \to \Bbb C$ on the abelian category $\mathcal{A}$, and another one is given in terms of slicings.

- $\mathcal{P}(\phi+1) = \mathcal{P}(\phi)[1]$.

- For all $\phi_1 > \phi_2$, we have $\operatorname{Hom}(\mathcal{P}(\phi_1),\mathcal{P}(\phi_2)) = 0$.

- For each $0 \ne E \in \mathcal{D}$ there exists real numbers $\phi_1 > \phi_2 > \cdots > \phi_n$, objects $E_i \in \mathcal{D}$, and a collection of triangles $$ \xymatrix{ 0=E_0 \ar@{->}[r] & E_1 \ar@{->}[r] \ar@{->}[d] & E_2 \ar@{->}[r] \ar@{->}[d] & \cdots \ar@{->}[r] & E_{n-1} \ar@{->}[r] \ar@{->}[d] & E_n=E \ar@{->}[d] \\ & A_1 \ar@{.>}[lu] & A_2 \ar@{.>}[lu] & & A_{n-1} \ar@{.>}[lu] & A_n \ar@{.>}[lu] } $$ with $A_i \in \mathcal{P}(\phi_i)$. This is called the Harder-Narasimhan filtration of $E$.

The benefit of slicings is that these do not require the choice of a heart of a $t$-structure upfront.

The following proposition gives us the freedom to choose which perspective to take:

I won’t go into the full details of the proof, but here are the key points. Given a stability condition $(Z,\mathcal{P})$, $\mathcal{A} = \mathcal{P}((0,1])$ defines a heart of a bounded $t$-structure. The central charge $Z$ is a stability function on $\mathcal{A}$ when we identify $K_0(\mathcal{A})$ with $K_0(\mathcal{D})$, and the $Z$-semistable objects in $\mathcal{A}$ are precisely the objects of $\mathcal{P}(\phi)$ for $\phi \in (0,1]$. The Harder-Narasimhan filtration is obtained from the decomposition given in the definition for the slicing $\mathcal{P}$. Conversely, define a stability condition $\sigma = (Z,\mathcal{P})$ in the following way: for every $\phi \in (0,1]$, let $\mathcal{P}(\phi)$ be the full subcategory of $\mathcal{A}$ containing the $Z$-semistable objects $E$ in $\mathcal{A}$ with phase $\phi$ as well as the zero object of $\mathcal{D}$. For $\phi \in \Bbb R$. set $\mathcal{P}(\phi) = \mathcal{P}(\psi)[k]$, where $\psi \in (0,1]$, $k \in \Bbb Z$ and $\phi = \psi + k$. The pair $(Z,\mathcal{P})$ will then define a stability condition on $\mathcal{D}$.

Again, the standard example is given by considering $D^b(X)$ for a smooth projective curve $X$, the canonical $t$-structure $\textbf{Coh}(X)$ and $Z(\mathcal{E}) = -\deg(\mathcal{E}) + i\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E})$. Note that $K_0(X) \cong \Bbb Z \oplus \operatorname{Pic}(X)$ via $[\mathcal{E}] \mapsto (\operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E}), \det(\mathcal{E}))$ and $\operatorname{Pic}(X)$ splits non-canonically as $\Bbb Z \oplus \operatorname{Pic}^0(X)$ by choosing a line bundle of degree $1$ on $X$. Later on, we would like to describe all stability conditions where the charge $Z : K_0(X) \to \Bbb C$ factors through the map $K_0(X) \to \Bbb Z \oplus \Bbb Z, \mathcal{E} \mapsto (\deg(\mathcal{E}), \operatorname{rk}(\mathcal{E}))$. When $X \not\cong \Bbb P^1$, $\operatorname{Pic}^0(X)$ is an infinitely generated abelian group so there are many other charges on $K_0(X)$ yielding stability conditions.

So $K_0(X)$ can very large and complex, potentially an infinitely generated group, which can make computations and definitions difficult to work with. To make things more manageable, we “fix a finite-rank lattice” $\Lambda$ and a surjective homomorphism $v : K_0(X) \to \Lambda$. This lattice can be thought of as a finite-dimensional free abelian group, which serves as a target for a simpler and more computable version of the information encoded by $K_0(X)$. In the standard example with $D^b(X)$ and the heart $\textbf{Coh}(X)$, the homomorphism $v$ is typically given by the Chern character

\[\operatorname{ch} : K_0(X) \to H^\ast(X,\Bbb Q).\]- $\mathcal{P}$ is a slicing of $D^b(X)$, and

- $Z : \Lambda \to \Bbb C$ is an additive homomorphism,

- For any non-zero $E \in \mathcal{P}(\phi)$, we have $$ Z(v(E)) \in \exp(i\pi\phi)\Bbb R_{> 0}. $$

- For a fixed norm $\| \cdot \|$ on $\Lambda_{\Bbb R}$, we have $$\inf\left\{ \frac{|Z(v(E))|}{\|v(E)\|} : 0 \ne E \in \mathcal{P}(\phi), \phi \in \Bbb R \right\} > 0.$$

Note that giving a stability condition $(\mathcal{P},Z)$ on $D^b(X)$ is equivalent to giving a stability condition $(\mathcal{A},Z)$ in the sense we defined stability conditions for abelian categories, where $\mathcal{A}$ is the heart of a bounded $t$-structure on $D^b(X)$ satisfying

\[\inf\left\{ \frac{|Z(v(E))|}{\|v(E)\|} : 0 \ne E \in \mathcal{A} \text{ semistable} \right\} > 0.\]Recall that there exists no stability condition on $D^b(X)$ with heart $\mathcal{A} = \textbf{Coh}(X)$ or central charge $Z = -\deg + i\operatorname{rk}$ when $X$ has dimension at least two. This observation reveals the fundamental difficulty in the study of Bridgeland stability conditions: their existence. In order to find adequate hearts, one considers the process of tilting of t-structures, and candidate central charges $Z$ arise primarily out of physical input. The difficulty in understanding when a heart A is a candidate for some Bridgeland stability condition comes in proving the existence of Harder-Narasimhan filtrations. To do so, one often requires inequalities of Chern numbers known as generalied Bogomolov–Gieseker inequalities. I might discuss this in a later post when I have developed a better understanding of how these behave.

To wrap this up, we’ll cover Bridgeland’s deformation theorem. That is, the fact that the space of stability conditions can be given the structure of a complex manifold. Denote by $\operatorname{Stab}(X)$ the set of stability conditions on $D^b(X)$ with respect to $\Lambda$ and $v$. This set can be given a topology by considering the initial topology induced by the maps $(\mathcal{A}, Z) \mapsto Z, (\mathcal{A}, Z) \mapsto \phi^{+}(E)$ and $(\mathcal{A}, Z) \mapsto \phi^{-}(E)$. The main result Bridgeland shows in “Spaces of stability conditions” is that the following:

A quick remark here: in the more general case with the space $\operatorname{Stab}(\mathcal{D})$ of stability conditions on a triangulated category $\mathcal{D}$, there is no reason to expect that $\operatorname{Stab}(\mathcal{D})$ is finite-dimensional. When we fix the lattice $\Lambda$ and the map $v$, we avoid the issue of having to deal with an infinite-dimensional space.

There are two group actions one can consider in the space of stability conditions. The first one is given by the universal cover $\widetilde{\mathrm{GL}}^+(2,\Bbb R)$ of $\mathrm{GL}^+(2,\Bbb R)$. This space has an explicit description consisting of pairs $(M,f)$ with $M \in \mathrm{GL}^+(2,\Bbb R)$ and $f$ increasing and satisfying $f(\phi+1) = f(\phi) + 1$ for all $\phi \in \Bbb R$ as well as $M \cdot \exp(i\pi\phi) \in \exp(i\pi f(\phi)) \Bbb R_{> 0}$. The latter condition simply states that the restrictions of $M$ and $f$ on $\Bbb R/2\Bbb Z$ coincide. The action is given by

\[(M,f)\cdot (\mathcal{P},Z) = (\mathcal{P}', M'),\]where $\mathcal{P}’(\phi) = \mathcal{P}(f(\phi))$ and $Z’ = M^{-1} \circ Z$. The second action is given by considering any linear exact autoequivalence $\Phi$ of $D^b(X)$. That is, $\Phi \in \operatorname{Aut}_\Lambda(D^b(X))$. This induces an action on the Grothendieck group $K_0(X)$ by $[E] \to [\Phi(E)]$ and then $\operatorname{Aut}_\Lambda(D^b(X))$ acts on $\operatorname{Stab}(X)$ via

\[\begin{align*} \operatorname{Aut}_\Lambda(D^b(X)) &\times \operatorname{Stab}(X) \to \operatorname{Stab}(X) \\ (\Phi, (\mathcal{P}, Z)) &\mapsto (\mathcal{P}', Z \circ \Phi^{-1}), \end{align*}\]with $\mathcal{P}’ = \Phi(\mathcal{P}(\phi))$. In the paper “Derived automorphism groups of $K3$ surfaces of Picard rank $1$” Bayer and Bridgeland utilize this action and the geometry of the space of stability conditions on $K3$ surfaces having Picard rank $1$ to obtain a complete description of the group of exact autoequivalences of the bounded derived category of coherent sheaves on such spaces. Bridgeland conjectures in “Stability conditions on $K3$ surfaces” that this should work for all $K3$ surfaces.

This spaces are relatively difficult to study, but in for example, $\operatorname{Stab}(\Bbb P^1) \cong \Bbb C^2$ as pointed out in the paper “Stability manifold of $\Bbb P^1$” by Okada. In the case of curves, if $X$ has genus $g \ge 1$, then $\operatorname{Stab}(X) \cong \Bbb H \times \Bbb C$.

A few words on the construction of stability conditions before we end this. These involve a major theme of torsion pairs and tilting which I have not covered in detail here for now. For $\dim X =1$, we have a complete description of $\operatorname{Stab}(X)$. In dimension two, Bridgeland constructed stability conditions on $K3$ surfaces in the following manner: for an ample class $\omega \in \operatorname{NS}(X)_\Bbb R$ and a class $B \in \operatorname{NS}(X)_\Bbb R$, consider

\[Z_{\omega,B} = -\int_X \exp(-i\omega)\operatorname{ch}^B.\]Using an appropriately chosen torsion pair, one can construct a heart $\textbf{Coh}^B(X)$ for this central charge by tilting $\textbf{Coh}(X)$. It then follows from the following Bogomolov-Gieseker inequality:

that the pair $(\textbf{Coh}^B(X), Z_{\omega,B})$ forms an Bridgeland stability condition on $X$. Its worth mentioning here that this strategy can be generalized to any smooth projective surface.

In dimension three, Bayer, Macrì, and Toda proposed a candidate stability condition defined by the central charge $Z_{\omega,B}$ and a structure known as the double-tilted heart $\mathcal{A}^{\omega,B}$. This heart is constructed by tilting the category $\textbf{Coh}^B(X)$ with respect to a specific torsion pair. The key in proving that $(Z_{\omega,B}, \mathcal{A}^{\omega,B})$ yields a Bridgeland stability condition lies in the following Bogomolov-Gieseker type inequality conjectured by Bayer, Macrì, and Toda:

The shown inequality does not hold for all threefolds, Schmidt provides a counterexample in “Counterexample to the Generalized Bogomolov-Gieseker Inequality for Threefolds” by considering the blow-up of a point over three dimensional projective space.

Dimension three is particularly significant because it allows the application of stability conditions in string theory, aligning with Bridgeland’s original intentions. One needs to prove the existence of stability conditions on $D^b(X)$, when $X$ is a compact Calabi-Yau threefold. It took more than a decade before the first example was produced by Li in “On stability conditions for the quintic threefold”. Li utilized a modified version of the conjectured inequality to obtain examples of stability conditions on Calabi-Yau threefolds.

In general one could use this tilting method to produce stability conditions $(Z_{\omega,B}, \mathcal{A}^{\omega,B}_{n-1})$ on $X$ for any dimension $n$ by tilting $\textbf{Coh}(X)$ $(n-1)$-times to get the heart $\mathcal{A}^{\omega,B}_{n-1}$. However, at each step one has to prove a condition similar to the conjectured inequality.

Next time, we’ll discuss walls and chambers.

-

Essentially a subcategory that is closed with respect to subobjects, quotients and extensions. ↩

-

This construction generalizes further: when $\mathcal{A} \subset \mathcal{D}$ is the heart of a bounded $t$-structure on a triangulated category $\mathcal{D}$, and $\mathcal{A}$ is both Noetherian and Artinian, any group homomorphism $Z : K_0(\mathcal{A}) \to \Bbb C$ with $Z(S) \in H := \{ 0 \ne z \in \Bbb C \mid z/|z| = \exp(i\pi\phi), 0 < \phi \le 1\}$, for all simple objects $S \in \mathcal{A}$, extends uniquely to a stability condition on $\mathcal{D}$. ↩