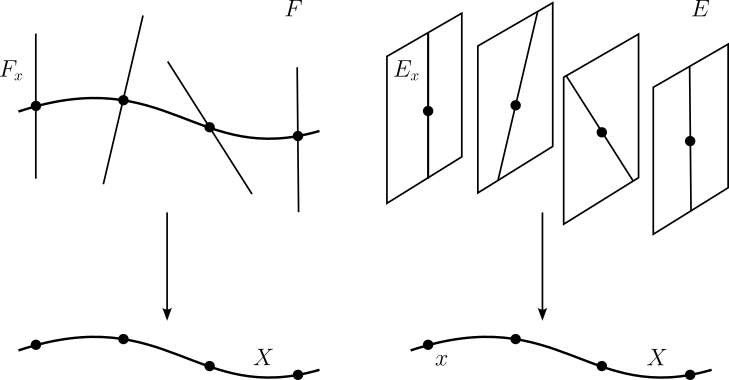

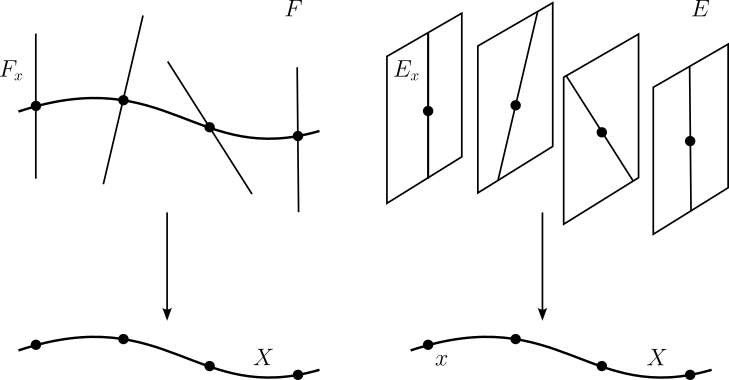

This is going to be one on line bundles and divisors. We’ll begin with the simplest line bundle one can consider which we’ll denote by $\mathcal{O}(-1)$ for reasons that become apparent soon. First, a lemma we’ll need. Recall that given a holomorphic vector bundle $E$ over a complex manifold $X$, a subset $F \subset E$ is called a holomorphic subbundle of $E$ if it is a complex submanifold of $E$, and satisfies the following conditions: for each point $x \in X$, the fiber $F_x = F \cap E_x$ is a linear subspace of $E_x$, with a fixed dimension $d$ across all points of $X$. Moreover, the restricted projection $F \to X$ defines a holomorphic vector bundle over $X$.

Let $X$ be a complex manifold and $\pi : E \to X$ a holomorphic vector bundle. Suppose that for any $x \in X$, there exists an $m$-dimensional linear subspace $F_x \subset E_x$. Then $F = \bigcup_{x \in X} F_x \subset E$ is a holomorphic subbundle of $E$ if and only if each $x \in X$ has a neighborhood over which there are holomorphic sections $s_1,\dots,s_m$ of $E$ such that $(s_1(y),\dots,s_m(y))$ forms a basis for $F_y$ for each $y \in X$.

If $F$ is a holomorphic subbundle, then by definition each $x \in X$ has a neighborhood $U$ over which there exists a holomorphic local trivialization of $F$. Associating this local trivialization with its corresponding local frame we obtain a holomorphic local frame $(e_1,\dots,e_m)$ for $F$ over each such $U$. Composing these with the inclusion $\iota : F \hookrightarrow E$, we obtain the desired frame $(s_1,\dots,s_m)$ where $s_i = \iota \circ e_i$. Conversely, suppose that for any $x \in X$ there exists a neighborhood over which there are holomorphic sections $s_1,\dots,s_m$ of $E$ such that $(s_1(y),\dots,s_m(y))$ forms a basis for $F_y$ for each $y \in X$. Each $F_x$ is a linear subspace of $E_x$ by hypothesis, so we are to show that $F$ is an embedded submanifold with or without boundary in $E$ and that the restriction of the projection $E \to X$ makes $F$ into a holomorphic vector bundle. To prove that $F$ is an embedded submanifold, it is sufficient to show that any $x \in X$ has a neighborhood $U$ such that $F \cap \pi^{-1}(U)$ is an embedded submanifold in $\pi^{-1}(U) \subset E$. For $x \in X$ and $U$ a neighborhood of $x$, consider holomorphic local sections $s_1,\dots,s_m$ of $E$ satisfying the condition stated in our hypothesis. Complete this to a holomorphic local frame $(s_1,\dots,s_k)$ for $E$, where $k = \operatorname{rk}(E)$. Consider now the associated trivialization

$$

\begin{align*}

\varphi : \pi^{-1}(U) &\to U \times \Bbb C^k \\

(y,v) &= \left(y, \sum_{i=1}^k v^is_i(y)\right) \mapsto (y,(v^1,\dots,v^k)).

\end{align*}

$$

This maps $F \cap \pi^{-1}(U)$ to the subset of $U \times \Bbb C^k$ consisting of points of the form $$(y,(v^1,\dots,v^m,0,\dots,0)),$$ which is an embedded submanifold. Moreover, the map $\psi : F \cap \pi^{-1}(U) \to U \times \Bbb C^k$ given by

$$

(y,v^1s_1(y),\dots,v^ms_m(y)) \mapsto (y,(v^1,\dots,v^m))

$$

is a holomorphic local trivialization of $F$ and hence $F$ is a holomorphic vector bundle.

Define now $\mathcal{O}(-1) \to \Bbb P^n$ as the subbundle

\[\mathcal{O}(-1) = \{(\ell, z) \in \Bbb P^n \times \Bbb C^{n+1} \mid z \in \ell\},\]

of the bundle $\Bbb P^n \times \Bbb C^{n+1}$.

The bundle $\mathcal{O}(-1) \to \Bbb P^n$ is a holomorphic line bundle.

Consider the usual cover for $\Bbb P^n$ given by the open sets $U_\alpha = \{[z^0:\dots:z^n] \in \Bbb P^n \mid z^\alpha \ne 0 \}$. On $U_\alpha$ we have a local holomorphic section $e_\alpha : U_\alpha \to \mathcal{O}(-1)$ given by

$$

e_\alpha([z^0:\cdots:z^n]) = \left([z], \frac{z^0}{z^\alpha},\dots, \frac{z^n}{z^\alpha} \right).

$$

This is nowhere-vanishing, spans the fiber of $\mathcal{O}(-1)$ at each point of $U_\alpha$ and hence $\mathcal{O}(-1)$ is a holomorphic line bundle by the lemma above.

The bundle $\mathcal{O}(-1) \to \Bbb P^n$ is called the tautological line bundle as the fibers of $\mathcal{O}(-1)$ at each point $\ell \in \Bbb P^n$ are exactly $\ell$.

Cover $\Bbb P^n$ with the open sets $U_\alpha = \{[z^0:\dots:z^n] \in \Bbb P^n \mid z^\alpha \ne 0 \}$ and let $e_\alpha : U_\alpha \to \mathcal{O}(-1)$ be the holomorphic section given by

$$

e_\alpha([z^0:\cdots:z^n]) = \left([z], \frac{z^0}{z^\alpha},\dots, \frac{z^n}{z^\alpha} \right).

$$

Then on $U_\alpha \cap U_\beta$, these sections satisfy $e_\beta = g_{\alpha\beta}e_\alpha$, where

$$

g_{\alpha\beta}([z]) = \frac{z^\alpha}{z^\beta}.

$$

Consider the overlap $U_\alpha \cap U_\beta$ where both $z^\alpha$ and $z^\beta$ are non-zero. Then

$$

\begin{align*}

e_\beta([z]) &= \left([z], \frac{z^0}{z^\beta},\dots, \frac{z^n}{z^\beta} \right) \\

&= \left([z], \frac{z^\alpha}{z^\beta}\left(\frac{z^0}{z^\alpha},\dots, \frac{z^n}{z^\alpha}\right) \right) \\

&= g_{\alpha\beta}([z])e_\alpha([z]).

\end{align*}

$$

Note that this gives also the transition functions for $\mathcal{O}(1) := \mathcal{O}(-1)^\ast$, $\mathcal{O}(-k)$ and $\mathcal{O}(k)$ as

\[\begin{align*}

g_{\alpha\beta}([z])^{-1} &= \frac{z^\beta}{z^\alpha}, \\

g_{\alpha\beta}([z])^{k} &= \left(\frac{z^\alpha}{z^\beta}\right)^k, \\

g_{\alpha\beta}([z])^{-k} &= \left(\frac{z^\beta}{z^\alpha}\right)^k

\end{align*}\]

respectively.

Let’s now consider the sections of various line bundles over the projective space. We’ll begin with $\mathcal{O}(-1)$.

The tautological line bundle $\mathcal{O}(-1) \to \Bbb P^n$ has no non-trivial global holomorphic sections.

Let $s : \Bbb P^n \to \mathcal{O}(-1)$ be a holomorphic section. For any $\ell \in \Bbb P^n$ we have

$$

s(\ell) = (\ell, z_\ell),

$$

for some $z_\ell \in \Bbb C^{n+1}$ lying on $\ell$. Hence $\ell \mapsto z_\ell$ is a holomorphic map $\Bbb P^n \to \Bbb C^{n+1}$. The maximum principle yields that this map is constant and so $z_\ell$ is given by some constant $w \in \Bbb C^{n+1}$ for every $\ell$. Now $s$ is fiber preserving and so $w \in \ell$ for each $\ell \in \Bbb P^n$, but only $0$ satisfies this and so $w = 0$.

We’ll consider the dual $\mathcal{O}(1)$ next.

Let $X$ be a complex manifold and $L \to X$ a holomorphic line bundle. For each positive integer $d$, the tensor product $(L^\ast)^{\otimes d}$ is naturally isomorphic to the bundle whose fiber at a point $x \in X$ is the space of functions $\varphi : L_x \to \Bbb C$ that are homogeneous of degree $d$. Furthermore, if $e : U \to L$ is a holomorphic global frame for $L$, then a local section $s$ of $(L^\ast)^{\otimes d}$ is holomorphic on $U$ if and only if the map

$$

x \mapsto s(e(x))

$$

is holomorphic.

The fiber $L^\ast_x \otimes \cdots \otimes L^\ast_x$ over $x \in X$ is naturally isomorphic to the space

$$

\operatorname{Hom}(L_x \otimes \cdots \otimes L_x, \Bbb C)

$$

of $d$-linear maps from $L_x \times \cdots \times L_x$ to $\Bbb C$. Now each such map $\varphi$ gives the existence for a homogeneous map

$$

\begin{align*}

\widetilde{\varphi} : L_x &\to \Bbb C \\

v &\mapsto \varphi(v,\dots,v).

\end{align*}

$$

Conversely if $\widetilde{\varphi}$ is such a homogeneous map, since $L_x$ is of dimension $1$, choosing a basis $b$ for $L_x$ one recovers $\varphi$ by defining

$$

\varphi(b,\dots,b) = \widetilde{\varphi}(b).

$$

Suppose then that $e$ is a local holomorphic frame for $L$ and let $\varepsilon$ denote the dual frame for $L^\ast$. Then

$$

\varepsilon^{\otimes d} = \varepsilon \otimes \cdots \otimes \varepsilon

$$

is a holomorphic local frame for $\left(L^\ast\right)^{\otimes d}$ with $\varepsilon^{\otimes d}(e) = 1$. If $s$ is a holomorphic local section of $(L^\ast)^{\otimes d}$, then the composition $s \circ e$ is holomorphic. Conversely, if $s$ is a local section of $(L^\ast)^{\otimes d}$ and $x \mapsto s(e(x))$ is holomorphic, then $s = f \varepsilon^{\otimes d}$ for some function $f : U \to \Bbb C$ and

$$

s(e(x)) = f(x)\varepsilon^{\otimes d}(e(x)) = f(x),

$$

i.e. $f$ is holomorphic and so is $s$.

The lemma above allows us to construct non-trivial sections for $\mathcal{O}(1)$ and its tensor powers. For $d \ge 1$, the fiber $ \ell^\ast \otimes \cdots \otimes \ell^\ast$ of $\mathcal{O}(d)$ can be identified with the space of homogeneous functions $\ell \to \Bbb C$ of degree $d$. To construct a section of $\mathcal{O}(d)$, begin with a homogeneous holomorphic polynomial

\[f : \Bbb C^{n+1} \to \Bbb C\]

of degree $d$. We can now restrict $f$ to each $1$-dimensional subspace of $\Bbb C^{n+1}$ and define $\sigma_f : \Bbb P^n \to \mathcal{O}(d)$ via

\[\sigma_f(\ell) = f\vert_{\ell}.\]

To see that this section is holomorphic, we’ll utilize the lemma above. Consider $U_\alpha = \{z^\alpha \ne 0 \}$, and the usual local frame $e_\alpha : U_\alpha \to \mathcal{O}(-1)$. Then

\[\sigma_f(e_\alpha([z^0:\cdots:1:\cdots:z^n])) = f\left(\frac{z^0}{z^\alpha},\dots,\frac{z^n}{z^\alpha}\right) = \frac{1}{(z^\alpha)^d}f(z^0,\dots,z^n)\]

and since $z^\alpha \ne 0$ on $U_\alpha$, $[z^0:\cdots:1:\cdots:z^n]\mapsto \sigma_f(e_\alpha([z^0:\cdots:1:\cdots:z^n]))$ is holomorphic and so is $\sigma_f$. The neat thing is that we have actually produced all of the non-trivial holomorphic sections of tensor powers of $\mathcal{O}(1)$.

Let $\mathcal{O}(1) \to \Bbb P^n$ be the dual of the tautological line bundle. Then the global holomorphic sections of tensor powers of $\mathcal{O}(1)$ are given as follows:

-

$H^0(\Bbb P^n, \mathcal{O}(-d)) = 0$.

-

$H^0(\Bbb P^n, \mathcal{O}(0)) \cong \Bbb C$

-

$H^0(\Bbb P^n, \mathcal{O}(d)) \cong \{ \sigma_f \mid f \in \Bbb C[z^0,\dots,z^n]_d \}$.

-

Recall that $\mathcal{O}(-1)$ has no non-trivial global holomorphic sections. Suppose that $\sigma$ is a non-trivial global holomorphic section of $\mathcal{O}(-d)$ for $d \ge 2$. Then as $\mathcal{O}(d-1)$ has a non-trivial section say $s_f$ obtained from some degree $d-1$ homogeneous polynomial $f$, the product $\sigma \otimes s_f$ is a holomorphic section of $\mathcal{O}(-1)$, but $H^0(\Bbb P^n, \mathcal{O}(-1)) = 0$ which is a contradiction.

-

Recall that if $\mathcal{O}(-1)$ has transition functions $g_{\alpha\beta}$, then $\mathcal{O}(d)$ and $\mathcal{O}(-d)$ have transition functions $g^{d}_{\alpha\beta}$ and $g^{-d}_{\alpha\beta}$ respectively. As $\mathcal{O}(0) \cong \mathcal{O}(d) \otimes \mathcal{O}(-d)$, the transition functions for $\mathcal{O}(0)$ are trivial and the global sections are just holomorphic maps $\Bbb P^n \to \Bbb P^n \times \Bbb C$ which we can identify with holomorphic maps $\Bbb P^n \to \Bbb C$ and as $\Bbb P^n$ is compact and connected these are just constants.

-

We've seen that every homogeneous holomorphic degree $d$ polynomial yields a holomorphic section $\sigma_f$ of $\mathcal{O}(d)$. We're left to show the converse. Suppose that $s \in H^0(\Bbb P^n, \mathcal{O}(d))$ is a holomorphic section. Then for any $[z] \in \Bbb P^n$

$$

s([z]) \in \ell^\ast \otimes \cdots \otimes \ell^\ast,

$$

where $\ell$ is the line corresponding to $[z]$. Under our identification of $\ell^\ast \otimes \cdots \otimes \ell^\ast$ with homogeneous maps $\ell \to \Bbb C$, we'll view $s([z])$ as such and define

$$

\begin{align*}

f : \Bbb C^{n+1} \setminus \{0\} &\to \Bbb C \\

z &\mapsto s([z])(z).

\end{align*}

$$

Hartogs’s extension theorem extends $f$ to a holomorphic function $\Bbb C^{n+1} \to \Bbb C$ which satisfies $f(\lambda z) = \lambda^df(z)$ for all $z \in \Bbb C^{n+1} \setminus \{0\}$, and hence also for $z = 0$ by continuity. The claim is now that $f$ is actually a polynomial. For $0 \ne z \in \Bbb C^{n+1}$ we have

$$

|f(z)| = |z|^d\left|f\left(\frac{z}{|z|}\right)\right| \le \sup_{|z|=1}|f(z)|z|^d.

$$

This implies that the Taylor series of $f$ at the origin has no terms of order less than $d$. Let $p$ be the polynomial consisting of only the terms of degree $d$ in the Taylor series of $f$ at $0$:

$$

p(z) = \sum_{k_1+\cdots+k_n = d} a_{k_1\dots k_n}(z^1)^{k_1}\cdots(z^n)^{k_n},

$$

and let $r(z) = f(z) - p(z)$. Now $r$ is homogeneous of degree $d$ as both $f$ and $p$ are, and since the Taylor series of $r$ starts with terms of order $d+1$, there exists a constant $M$ such that $|r(z)| \le M|z|^{d+1}$ for all $z$ in the closed unit ball. For any $z \in \Bbb C^{n+1}$ and small enough $\varepsilon > 0$ such that $|\varepsilon z| \le 1$, we have

$$

|r(z)| = \varepsilon^{-d}|r(\varepsilon z)| \le \varepsilon^{-d}M|z|^{d+1} = \varepsilon M|z|.

$$

We conclude that $r(z) = 0$ as $\varepsilon \to 0$ and hence $f = p$ and $s = \sigma_f$.

Let’s now focus on the relations between line bundles and hypersurfaces. In $\Bbb C^n$ we have the freedom to describe hypersurfaces as regular level sets of globally defined holomorphic functions, but this is not the case when $X$ is a compact complex manifold as such maps would be constant. The remedy is to use sections of line bundles.

Suppose that $X$ is a complex manifold and $L \to X$ is a holomorphic line bundle. For $s \in H^0(X,L)$, the zero set of $s$ is the set

\[V_s = \{x \in X \mid s(x) = 0\}.\]

The section $s$ is said to vanish simply if whenever we have a local frame $e$ for $L$, we can express $s = fe$ where $df_p \ne 0$ whenever $f(p) = 0$. Note that this condition is independent of the frame and that this is equivalent to saying that the vanishing of $s$ defines a smooth, codimension-one submanifold of $X$ locally, in analogy with regular level sets of smooth functions. For complex manifolds, this ensures that the zero locus $V_s$ is a divisor, which can be thought of as a hypersurface in $X$.

Consider a homogeneous polynomial $f: \mathbb{C}^{n+1} \to \mathbb{C}$ of degree $d$. Such a polynomial defines a projective variety $V \subset \mathbb{P}^n$ as its zero locus in projective space. Additionally, $f$ induces a holomorphic section $\sigma_f$ of the line bundle $\mathcal{O}(d)$ over $\mathbb{P}^n$, so that the variety $V$ can be expressed as $V = V_{\sigma_f}$, the zero set of the section $\sigma_f$.

When the degree $d = 1$, the zero loci of holomorphic sections of $\mathcal{O}(1)$ are precisely the projective hyperplanes in $\mathbb{P}^n$. Consequently, the line bundle $\mathcal{O}(1)$ is commonly referred to as the hyperplane bundle.

More generally, any closed complex hypersurface can be described as the zero set of a holomorphic section of a line bundle. Specifically, let $X$ be a complex manifold and $Y \subset X$ a closed complex hypersurface. A system of local defining functions for $Y$ consists of an open cover ${ U_\alpha }$ of $X$ together with holomorphic functions $f_\alpha: U_\alpha \to \mathbb{C}$ such that each $f_\alpha$ vanishes exactly on the intersection $Y \cap U_\alpha$ and nowhere else within $U_\alpha$.

This framework allows us to understand complex hypersurfaces in terms of holomorphic sections of line bundles, providing a powerful tool for studying their geometric and topological properties.

Let $X$ be a complex manifold and $Y \subset X$ a complex hypersurface. If $U \subset X$ is open and $f_1,f_2 : U \to \Bbb C$ are holomorphic functions that vanish simply on $Y \cap U$ and nowhere else, then there exists a holomorphic function $h : U \to \Bbb C$ such that $f_2 = hf_1$.

Since both $f_1$ and $f_2$ vanish exactly on $Y \cap U$ and do not vanish elsewhere in $U$, on the open set $U \setminus Y$, $f_1$ is nowhere zero. Therefore, we can define a function $h$ on $U \setminus Y$ by

$$

h = \frac{f_2}{f_1}.

$$

This function $h$ is holomorphic on $U \setminus Y$ because it is the quotient of two holomorphic functions where the denominator does not vanish. To extend $h$ to a holomorphic function on the entire open set $U$ consider $p \in Y \cap U$ and choose local holomorphic coordinates $(z^1,\dots,z^n)$ on a neighborhood $V$ of $p$ such that $Y \cap V$ is the set where $z^n = 0$. Since $f_1(z^1,\dots,z^{n-1},0)$ is identically zero, the Taylor series of $f_1$ centered at any point of $Y \cap V$ has no terms of order zero in $z^n$, and hence we can factor out $z^n$ to write $f_1(z)=z^ng_1(z)$ for some holomorphic function $g_1$. As $f_1$ vanishes simply on $Y \cap U$, $df_1$ is non-vanishing at the points where $z^n = 0$ and so $g_1 \ne 0$ on $Y \cap V$. Similar argument gives $f_2(z) = z^ng_2(z)$ and so in $V \setminus Y$,

$$

\frac{f_2}{f_1} = \frac{g_2}{g_1}.

$$

This extends to a non-vanishing holomorphic function on all of $V$ and since the complement of $Y$ is dense in $U$, the extension is unique by continuity. Thus $f_2/f_1$ extends uniquely to a nonvanishing holomorphic function in a neighborhood of each point of $U$, and by uniqueness, the extensions all fit together to determine a nowhere-vanishing holomorphic function $h : U \to \Bbb C$ satisfying $f_2 = hf_1$.

The next theorem gives the association between line bundles and hypersurfaces.

Let $X$ be a complex manifold and $Y \subset X$ a closed complex hypersurface. Then there exists a holomorphic line bundle $\mathcal{O}(Y) \to X$, called the associated line bundle for $Y$, and a holomorphic section $s \in H^0(X,\mathcal{O}(Y))$ such that $s$ vanishes simply on $Y$ and nowhere else. Any two line bundles that admit holomorphic sections vanishing simply on $Y$ are isomorphic.

Consider a local defining system $\{(U_\alpha, f_\alpha)\}$ for $Y$. When $U_\alpha \cap U_\beta \ne \emptyset$, the previous lemma applied to $f_\alpha,f_\beta : U_\alpha \cap U_\beta \to \Bbb C$ yields a nowhere-vanishing holomorphic function

$$

g_{\alpha\beta} : U_\alpha \cap U_\beta \to \Bbb C^\ast \cong \mathrm{GL}(1,\Bbb C)

$$

such that

$$

g_{\alpha\beta} = \frac{f_\alpha}{f_\beta}

$$

on the complement of $Y$. On triple intersections $U_\alpha \cap U_\beta \cap U_\gamma \ne 0$, we have

$$

g_{\alpha\beta}g_{\beta\gamma} = g_{\alpha\gamma}

$$

on the complement of $Y$ and the same holds by continuity on all of $U_\alpha \cap U_\beta \cap U_\gamma$. This yields the transition data which we can apply to obtain a holomorphic line bundle $\mathcal{O}(Y) \to M$, with trivializations over each $U_\alpha$ and transition functions $g_{\alpha\beta}$. Consider now a holomorphic section $s : X \to \mathcal{O}(Y)$ given by

$$

s(x) = f_\alpha(x)e_\alpha(x),

$$

where $x \in U_\alpha$ and $e_\alpha : U_\alpha \to \mathcal{O}(Y)$ is given by the local frame corresponding to the trivializing open cover $\{U_\alpha\}$ for $\mathcal{O}(Y)$. It follows that $Y$ is the zero loci of $s$ is exactly $Y$ and $s$ vanishes simply on $Y$. To see that any to such bundles are isomorphic, suppose that $L \to X$ is another holomorphic line bundle and $\widetilde{s} : X \to L$ a holomorphic section that vanishes simply on $Y$ and nowhere else. Choose a trivializing open cover $\{U_\alpha \}$ that trivializes both bundles $\mathcal{O}(Y)$ and $L$. Let $e_\alpha : U_\alpha \to \mathcal{O}(Y)$ and $\widetilde{e}_\alpha : U_\alpha \to L$ be holomorphic local frames and $g_{\alpha\beta}, \widetilde{g}_{\alpha\beta}$ the corresponding transition functions. On each $U_\alpha$ we have

$$

s = f_\alpha e_\alpha, \quad \text{and} \quad \widetilde{s} = \widetilde{f}_{\alpha}\widetilde{e}_\alpha,

$$

for holomorphic functions $f_\alpha$ and $\widetilde{f}_\alpha$ that vanish simply on $Y$. Now $\tau_\alpha := \widetilde{f}_\alpha/f_\alpha$ extends to a non-vanishing holomorphic function on all of $U_\alpha$ and on the intersection $U_\alpha\cap U_\beta$ we have

$$

s = f_\alpha e_\alpha = f_\beta e_\beta = f_\beta g_{\alpha\beta}e_\alpha

$$

so $f_\alpha = f_\beta g_{\alpha\beta}$. Likewise, $\widetilde{f}_\beta = \widetilde{f}_\beta \widetilde{g}_{\alpha\beta}$. On $(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta) \setminus Y$, we obtain

$$

g_{\alpha\beta} = \frac{\widetilde{f}_\alpha f_{\beta} g_{\alpha\beta}}{\widetilde{f}_\alpha f_\beta} = \frac{\widetilde{f}_\beta\widetilde{g}_{\alpha\beta}f_\alpha}{\widetilde{f}_\alpha f_\beta} = \tau^{-1}_\alpha\widetilde{g}_{\alpha\beta}\tau_{\beta},

$$

and this holds on all of $U_\alpha \cap U_\beta$ by continuity. Hence $L \cong \mathcal{O}(Y)$.

In the case when $Y \subset \Bbb P^n$ is a projective algebraic hypersurface defined by a single homogeneous polynomial of degree $d$, we obtain a global holomorphic section $s$ of $\mathcal{O}(d)$ that vanishes simply on $Y$ and nowhere else. Hence $\mathcal{O}(Y) \cong \mathcal{O}(d)$ by the theorem above.

Finally, we’ll focus on divisors and establish the relationship with line bundles. To sort of motivate this, let $X \subset \Bbb P^N$ be a holomorphic manifold embedded in projective space. A hyperplane section of $X$ is the intersection of $X$ with a hyperplane in $\Bbb P^N$. These hyperplane sections provide valuable information about how $X$ is embedded in the projective space. Conversely, for any given holomorphic manifold, it is important to intrinsically describe and classify its “hyperplane sections.” The appropriate mathematical structures for this purpose are known as divisors. Divisors, along with meromorphic functions and line bundles, represent essentially the same data from different perspectives: geometric, algebraic, and topological. This trinity allows us to understand the manifold’s intrinsic properties and its embeddings.

As observed in the previous theorem, hypersurfaces are always given as the zero locus of a global holomorphic section of a holomorphic line bundle. This allows us to study the codimension one geometry of a compact complex manifold by means of holomorphic line bundles, their space of global sections, and, eventually, their

cohomology.

Suppose that $Y \subset X$ is a hypersurface. Then $Y$ is given by the union $\bigcup_i Y_i$ of its irreducible components. Generally speaking, this union is only locally finite.

A divisor $D$ on $X$ is a locally finite formal linear combination

$$

D = \sum_i a_i[Y_i],

$$

where each $Y_i \subset X$ is an irreducible hypersurface, and $a_i \in \Bbb Z$.

By locally finite we mean that for any $x \in X$, there exists a neighborhood $U \ni x$ such that only finitely many irreducible hypersurfaces $Y_i$ intersect $U$ non-trivially. In other words, there are only finitely many indices $i$ for which $a_i \ne 0$ and $Y_i \cap U \ne \emptyset$. Note that the set of divisors $\operatorname{Div}(X)$ has a natural group structure. Clearly, any hypersurface $Y = \bigcup_i Y_i$ defines a divisor $\sum_i [Y_i] \in \operatorname{Div}(X)$. Conversely, given a divisor $D = \sum_i a_i [Y_i]$, we can associate it with the underlying hypersurface $\bigcup_i Y_i$. However, this association does not retain the multiplicities $a_i$ of the components.

A divisor $D = \sum a_i[Y_i]$ is called effective if $a_i \ge 0$ for all $i$. We express this symbolically as $D \ge 0$.

As an example, the divisor $D = \sum [Y_i]$ associated with a hypersurface $Y = \bigcup_i Y_i$ is an effective divisor.

Let’s quickly recall the definition of a meromorphic function on a complex manifold.

Let $X$ be a complex manifold. A meromorphic function on $X$ is a map

$$

f : X \to \bigsqcup_{x \in X} \operatorname{Frac}(\mathcal{O}_{X,x})

$$

that assigns to each $x \in X$ an element $f_x$ in the field of fractions of the local ring $\mathcal{O}_{X,x}$ satisfying the following condition: For every $x_0 \in X$, there exists an open neighborhood $U \ni x_0$ and holomorphic functions $g,h : U \to \Bbb C$ such that

$$

f_x = \frac{g}{h} \quad \text{for all } x \in U.

$$

We will denote the sheaf of meromorphic functions on $X$ by $\mathcal{K}_X$.

A divisor $D$ is called a principal divisor if $D = (f)$ for some $f \in H^0(X,\mathcal{K}^\ast_X)$.

Let $Y \subset X$ be an irreducible hypersurface. Then if $x \in Y$, there exists open neighborhood $U \subset X$ of $x$ and a holomorphic function $f \in \mathcal{O}_X(U)$ such that $Y \cap U = f^{-1}(0) \cap U$. Such a $f$ map is called local defining function for $Y$.

Let $Y \subset X$ be an irreducible hypersurface, $x \in Y$, and $f$ a local defining function for $Y$ at $x$. Then for $g \in \mathcal{O}_{X,x}$, we define the order $\operatorname{ord}_{Y,x}(g)$ of $g$ along $Y$ at $x$ to be the largest integer $k$ such that

$$

g = f^k \cdot h

$$

in the local ring $\mathcal{O}_{X,x}$.

Note that since $\mathcal{O}_{X,x}$ is a UFD, the order is well-defined and always finite. Also as relatively prime elements of $\mathcal{O}_{X,x}$ stay relatively prime in nearby stalks, we conclude that the order $\operatorname{ord}_{Y,x}(g)$ is independent of $x$. Also if $g$ and $h$ are holomorphic around $x$, then

\[\operatorname{ord}_Y(gh) = \operatorname{ord}_Y(g) + \operatorname{ord}_Y(h).\]

Using this, we can define the order for meromorphic functions:

Let $X$ be a complex manifold and $f$ a meromorphic function. Let $Y \subset X$ be an irreducible hypersurface. Then the order of $f$ along $Y$ is defined by

$$

\operatorname{ord}_Y(f) := \operatorname{ord}_Y(g) - \operatorname{ord}_Y(h),

$$

where $f = g/h$ at some regular point of $Y$.

If $f$ is a meromorphic function on $f$ and $Y \subset X$ an irreducible hypersurface, we say that $f$ has a zero of order $d$ along $Y$ if $d = \operatorname{ord}_Y(f) > 0$ and that $f$ has a pole of order $-d$ along $Y$ if $d = \operatorname{ord}_Y(f) < 0$.

If $f \in H^0(X,\mathcal{K}^\ast)$, we define the divisor $(f)$ associated to $f$ as

$$

(f) := \sum_{Y} \operatorname{ord}_Y(f)[Y],

$$

where the sum is taken over all irreducible hypersurfaces $Y \subset X$.

A priori it may not be clear that the above sum actually is a divisor as we did not check that the sum is locally finite. However, this is indeed the case. If $x \in X$, then locally we can write $f$ as a fraction $g/h$ and there are only finitely many $Y$’s with $\operatorname{ord}_Y(g) \ne 0$. This can be concluded by using the fact that the stalk $\mathcal{O}_{X,x}$ is a UFD, and we can write $g$ as a product of finitely many irreducible elements. Note also that $(f)$ is effective if and only if $f$ is holomorphic.

Divisors $D$ and $D'$ are called linearly equivalent if $D - D'$ is effective.

As every holomorphic function is meromorphic, we can consider the inclusion $\mathcal{O}^\ast_X \subset \mathcal{K}^\ast_X$, and form a sheaf by sheafifying the quotient presheaf $\mathcal{K}^\ast_X/\mathcal{O}^\ast_X$. A global section $f \in H^0(X,\mathcal{K}^\ast_X/\mathcal{O}^\ast_X)$ consists of an open cover ${U_i}$ of $X$ and meromorphic functions $f_i \in \mathcal{K}^\ast_X(U_i)$ such that

\[\frac{f_i}{f_j} \in \mathcal{O}^\ast_X(U_i\cap U_j),\]

whenever $U_i\cap U_j \ne \emptyset$.

Let $X$ be a complex manifold. Then there exists an isomorphism

$$

H^0(X, \mathcal{K}^\ast_X/\mathcal{O}^\ast_X) \cong \operatorname{Div}(X).

$$

Let $f \in H^0(X, \mathcal{K}^\ast_X/\mathcal{O}^\ast_X)$. Then $f$ is given by meromorphic functions $f_i$ on an open cover $\{U_i\}$ of $X$ such that $f_i/f_j \in \mathcal{O}^\ast_X(U_i \cap U_j)$ if $U_i \cap U_j \ne \emptyset$. If $Y \subset X$ is an irreducible hypersurface with $Y \cap (U_i \cap U_j) \ne \emptyset $, then $f_i/f_j$ being holomorphic, we obtain

$$

0 = \operatorname{ord}_Y(f_i/f_j) = \operatorname{ord}_Y(f_i) - \operatorname{ord}_Y(/f_j),

$$

i.e. $\operatorname{ord}_Y(f_i) = \operatorname{ord}_Y(f_j)$. We can thus define $\operatorname{ord}_Y(f) := \operatorname{ord}_Y(f_i)$ for any $U_i$ with $Y \cap U_i \ne \emptyset$. This yields a map $H^0(X, \mathcal{K}^\ast_X/\mathcal{O}^\ast_X) \to \operatorname{Div}(X)$ given by

$$

f \mapsto \sum_Y \operatorname{ord}_Y(f)[Y],

$$

which is a group homomorphism as the order is additive. Suppose then that $D = \sum_i a_i[Y_i] \in \operatorname{Div}(X)$. Consider $Y_i$, then there is a local defining system $\{(U_j, g_{ij})\}$ for $Y_i$ such that

$$

Y_i \cap U_j = g^{-1}_{ij}(0).

$$

Define now

$$

f_j := \prod_{i} g^{a_i}_{ij}.

$$

This is a finite product as $D$ is locally finite. As $g_{ij}$ and $g_{ik}$ define the same hypersurface in $U_j \cap U_k$, we have that

$$

\frac{g_{ij}}{g_{ik}} \in \mathcal{O}^\ast_X(U_j \cap U_k).

$$

It follows that $f_j$'s glue to give a section of $H^0(X,\mathcal{K}^\ast_X/\mathcal{O}^\ast_X)$ and so we obtain an inverse $\operatorname{Div}(X) \to H^0(X,\mathcal{K}^\ast_X/\mathcal{O}^\ast_X)$ for the previously constructed map.

Using the above proposition, we’ll say that $D \in \operatorname{Div}(X)$ is given by the local datum $\{(U_i,f_i)\}$. In algebraic geometry, these are called Cartier divisors.

Let $X$ be a complex manifold. Then there exists a group homomorphism

$$

\begin{align*}

\operatorname{Div}(X) &\to \operatorname{Pic}(X) \\

D &\mapsto \mathcal{O}(D),

\end{align*}

$$

for which the kernel consists of the set of principal divisors.

Let $D \in \operatorname{Div}(X)$ be given by local data $\{(U_i,f_i)\}$ and consider $\tau_{ij} := \frac{f_i}{f_j} \in \mathcal{O}^\ast_X(U_i\cap U_j)$. These maps satisfy the cocycle conditions and hence generate an element $\mathcal{O}(D)$ of the group $\operatorname{Pic}(X) \cong H^1(X,\mathcal{O}^\ast_X)$. To show that the map from divisors to line bundles is well-defined, we need to prove that the line bundle \( \mathcal{O}(D) \) constructed from a divisor \( D \) does not depend (up to isomorphism) on the choice of local defining functions for \( D \).

Suppose \( D \) is a divisor on \( X \), and let \( \{ U_i \} \) be an open cover of \( X \) such that on each \( U_i \), we have two local defining functions \( f_i \) and \( \widetilde{f}_i \) for \( D \). This means that both \( f_i \) and \( \widetilde{f}_i \) are holomorphic functions on \( U_i \) that vanish along the hypersurfaces specified by \( D \), with multiplicities corresponding to \( D \).

Since \( f_i \) and \( \widetilde{f}_i \) define the same divisor \( D \)

\[

f_is_i = \widetilde{f}_i,

\]

for a a nowhere-vanishing holomorphic function $s_i$ on \( U_i \). The transition functions for the line bundles \( \mathcal{O}(D) \) and \( \widetilde{\mathcal{O}}(D) \) constructed from \( \{ f_i \} \) and \( \{ \widetilde{f}_i \} \) are given by

\[

\tau_{ij} = \frac{f_i}{f_j} \quad \text{and} \quad \widetilde{\tau}_{ij} = \frac{\widetilde{f}_i}{\widetilde{f}_j}

\]

on overlaps \( U_i \cap U_j \).

We observe that on \( U_i \cap U_j \):

\[

\begin{aligned}

\widetilde{\tau}_{ij} &= \frac{\widetilde{f}_i}{\widetilde{f}_j} = \frac{f_i / s_i}{f_j / s_j} = \left( \frac{s_j}{s_i} \right) \frac{f_i}{f_j} = \left( \frac{s_j}{s_i} \right) \tau_{ij}.

\end{aligned}

\]

Define \( \lambda_{ij} = s_j / s_i \), which is a nowhere-vanishing holomorphic function on \( U_i \cap U_j \). The collection \( \{ \lambda_{ij} \} \) satisfies the cocycle condition:

\[

\lambda_{ij} \lambda_{jk} = \left( \frac{s_j}{s_i} \right) \left( \frac{s_k}{s_j} \right) = \frac{s_k}{s_i} = \lambda_{ik},

\]

since:

\[

\lambda_{ij} \lambda_{jk} = \lambda_{ik} \quad \text{on} \quad U_i \cap U_j \cap U_k.

\]

Therefore, \( \{ \lambda_{ij} \} \) defines a line bundle \( L \) with transition functions \( \lambda_{ij} \).

Moreover, because \( s_i \) are nowhere-vanishing holomorphic functions on \( U_i \), we can define a global nowhere-vanishing holomorphic section \( s \) of \( L \) by setting \( s|_{U_i} = s_i \). On overlaps \( U_i \cap U_j \), we have:

\[

s_i = \lambda_{ij} s_j,

\]

which ensures that \( s \) is well-defined globally.

The existence of such a global nowhere-vanishing holomorphic section implies that \( L \) is a trivial line bundle.

Now, we can relate the line bundles \( \mathcal{O}(D) \) and \( \widetilde{\mathcal{O}}(D) \) via \( L \). From the relation between their transition functions:

\[

\widetilde{\tau}_{ij} = \lambda_{ij} \tau_{ij},

\]

we see that:

\[

\widetilde{\mathcal{O}}(D) \cong L \otimes \mathcal{O}(D).

\]

Since \( L \) is trivial, we have:

\[

\widetilde{\mathcal{O}}(D) \cong \mathcal{O}(D).

\]

This shows that the line bundle \( \mathcal{O}(D) \) constructed from \( D \) is independent of the choice of local defining functions, up to isomorphism. Therefore, the map \( D \mapsto \mathcal{O}(D) \) is well-defined. Next, we'll check that the map $D \mapsto \mathcal{O}(D)$ is a group homomorphism. Let $D, \widetilde{D} \in \operatorname{Div}(X)$ be given by local data $\{(U_i,f_i)\}$ and $\{(U_i,\widetilde{f}_i)\}$ respectively. The divisor $D + \widetilde{D}$ is now given by the local data $\{(U_i, f_{i}\widetilde{f}_i)\}$ and so

$$

\mathcal{O}(D + \widetilde{D}) \cong \mathcal{O}(D) \otimes \mathcal{O}(\widetilde{D}),

$$

from where we conclude that the map is a homomorphism. Lastly, we will show that the kernel of the homomorphism consists of principal divisors. Suppose that $D = (f)$, for $f \in H^0(X,\mathcal{K}^\ast)$ is a principal divisor. Consider then $\{(U_i,f_i)\}$, where $f_i = f\vert_{U_i}$. The transition maps for $\mathcal{O}(D)$ are then given by

$$

\tau_{ij} = \frac{f_i}{f_j} = 1

$$

on $U_i \cap U_j$. Hence $\mathcal{O}(D)$ is isomorphic to the trivial bundle. Conversely, let $D$ be in the kernel of the constructed homomorphism. That is, $\mathcal{O}(D) \cong \mathcal{O}_X$. Then there exists a global nowhere-vanishing holomorphic section $s \in \mathcal{O}(D)$. On each $U_i$ of an open cover $\{U_i\}$ of $X$, $s$ can be expressed in terms of a local frame $e_i$ for $\mathcal{O}(D)$ as

$$

s\vert_{U_i} = s_ie_i,

$$

where $s_i$ is a nowhere-vanishing holomorphic function on $U_i$. Recall that the transition maps for $\mathcal{O}(D)$ are given by

$$

\tau_{ij} = \frac{f_i}{f_j},

$$

where $f_i$'s are the local defining functions for $D$ on $U_i$. On overlaps $U_i \cap U_j$, the local frames are related by

$$

e_i = \tau_{ij}e_j = \frac{f_i}{f_j}e_j.

$$

Also $s_ie_i = s_je_j$ on $U_i \cap U_j$ and this gives

$$

s_ie_i = s_j\frac{f_j}{f_i}e_i,

$$

i.e. $s_i = s_j\left(f_j/f_i\right)$. Rewriting this we obtain

$$

\frac{f_i}{s_i} = \frac{f_j}{s_j}

$$

on $U_i \cap U_j$. It follows that $g_i := f_i/s_i$ on $U_i$ glue together to form a global meromorphic function $g$ on $X$ since they agree on overlaps and so $D = (g)$.

To wrap this up, let’s consider divisors in the simplest case on a compact Riemann surface $\Sigma$. We’ll start off with the following lemma:

Let $\Sigma$ be a compact Riemann surface and $L$ a holomorphic line bundle over $\Sigma$. For any $p \in \Sigma$, denote by $\mathcal{O}(p)$ the line bundle associated to the divisor $\{p\}$. Then

$$

\chi(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(-p)) = \chi(X, L) -1,

$$

and

$$

\chi(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(p)) = \chi(X, L) +1.

$$

Consider the short exact sequence of sheaves given by

$$

0 \longrightarrow \mathcal{I}_{p}(-,L) \longrightarrow H^0(-,L) \longrightarrow i_{p,\ast} L_p \longrightarrow 0,

$$

where $\mathcal{I}_{p}(-,L)$ is the ideal sheaf of holomorphic sections of $L$ that vanish at $p$ and $i_{p,\ast} L_p$ the skyscraper sheaf whose stalk at $p$ is $L_p$. For any $U \subset \Sigma$, the map $H^0(-,L) \to i_{p,\ast} L_p$ is given by evaluation of $s \in H^0(U,L)$ at $p$ if $p \in U$ and otherwise it is the zero map. Recall that $\mathcal{I}_p(-,L) \cong H^0(-, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(-p))$ and since $\Sigma$ is compact $H^0(-, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(-p))$ is finite-dimensional and hence the Euler characteristic for the sheaf $\mathcal{I}_Y(-,L)$ is defined. Also as skyscraper sheaves are fine, its cohomology vanishes at all degrees except for

$$

H^0(\Sigma, i_{p,\ast} L_p) \cong L_p.

$$

Thus

$$

\chi(X, i_{p,\ast} L_p) = \dim L_p = 1.

$$

As the Euler characteristic is additive over short exact sequences, we obtain

$$

\chi(X, L) = \chi(X, \mathcal{I}_{p}(-,L)) + 1 \cong \chi(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(-p)) + 1,

$$

i.e. $\chi(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(-p)) = \chi(X, L) -1$. The latter one follows now by applying $\chi(X, L) = \chi(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(-p)) + 1$ to $L \otimes \mathcal{O}(p)$. We get

$$

\chi(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(p)) = \chi(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}(p) \otimes \mathcal{O}(-p)) + 1 = \chi(X,L) + 1.

$$

Let $\Sigma$ be a compact Riemann surface. Then the map

\begin{align*}

\operatorname{Div}(\Sigma) &\to \operatorname{Pic}(\Sigma) \\

D &\mapsto \mathcal{O}(D)

\end{align*}

is surjective.

Let $L$ be a holomorphic line bundle over $\Sigma$. For any integer $q \ge 0$, the Dolbeault theorem states that

$$

H^{0,q}(X,L) \cong H^q(X,L),

$$

where $H^{0,q}(X,L)$ are the Dolbeault cohomology groups with coefficients in $L$ and $H^q(X,L)$ are the sheaf cohomology groups of the sheaf of sections of $L$. Now, on a Riemann surface, there are no non-trivial $(0,q)$-forms for $q \ge 2$ and so $H^q(X,L) = 0$ for $q \ge 2$. It follows that

$$

\chi(X,L) = \dim H^0(X,L) - \dim H^1(X,L).

$$

Let $p \in \Sigma$. Combining the previous lemma with an induction we obtain

$$

\chi(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(p)) = \chi(X,L) + k

$$

for any positive integer $k$. This gives

$$

\begin{align*}

\dim H^0(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(p)) &= \chi(X,L \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(p)) + \dim H^1(X, L \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(p)) \\

&\ge \chi(X,L \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(p)) \\

&= \chi(X, L) + k.

\end{align*}

$$

This is positive for sufficiently large $k$ and so we conclude that $L \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(p)$ has a non-trivial holomorphic section $s$. It follows that

$$

L \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(p) \cong \mathcal{O}(D),

$$

where $D$ is the divisor corresponding to $s$. Let $D'$ be the divisor $k[p]$, then since $\operatorname{Div}(\Sigma) \to \operatorname{Pic}(\Sigma)$ is a group homomorphism, $\mathcal{O}^k(p) \cong \mathcal{O}(D')$ and so $\mathcal{O}^k(-p) \cong \mathcal{O}(-D')$. This gives

$$

L \cong (L \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(p)) \otimes \mathcal{O}^k(-p) \cong \mathcal{O}(D) \otimes \mathcal{O}(-D') \cong \mathcal{O}(D-D').

$$

The degree of a complex line bundle $L \to \Sigma$ is defined to be the integer

\[\deg(L) = \langle c_1(L), [\Sigma]\rangle = \int_\Sigma c_1(L),\]

where $c_1(L)$ is the first Chern class of $L$ and $[\Sigma] \in H_2(\Sigma)$ is the fundamental class of $\Sigma$. The degree of a divisor $D = \sum_i a_i[p_i]$ on a Riemann surface is given by

\[\deg D = \sum_i a_i.\]

The following theorem gives us an easy way to compute degrees for line bundles over Riemann surfaces.

Let $\Sigma$ be a connected compact Riemann surface. For any divisor $D \in \operatorname{Div}(\Sigma)$, the degree of the line bundle $\mathcal{O}(D)$ is equal to the degree of the divisor $D$.

Let $D = \sum_i a_i[p_i] \in \operatorname{Div}(\Sigma)$. Then $\mathcal{O}(D)$ has a meromorphic section $s$ whose divisor equals $D$. Pick a Hermitian metric on $\mathcal{D}$, let $\nabla$ denote the corresponding Chern connection and let $\Omega \in \Omega^{1,1}(\Sigma, \operatorname{End}(E))$ denote its curvature form. For each $p_i$ pick a holomorphic coordinate $z^i$ on an open disc $U_i$ centered at $p_i$. For $\varepsilon > 0$, let $U_i(\varepsilon) \subset \Sigma$ be the set of points in $q \in U_i$ for which $|z^i(q)| < \varepsilon$. For small enough $\varepsilon$ such that $\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon) \subset U_i$ for any $i$ and the sets $\overline{U}_1(\varepsilon),\dots,\overline{U}_k(\varepsilon)$ are disjoint, let $\Sigma_\varepsilon = \Sigma \setminus (U_1(\varepsilon) \cup \cdots \cup U_k(\varepsilon))$. On $\Sigma \setminus \{p_1,\dots,p_k\}$, the section $s$ is holomorphic and non-vanishing, so it can be used as a holomorphic frame for $L$ to compute $\Omega$. As in

Holomorphic Connections and The Atiyah Class

We obtain

$$

\Omega = \bar{\partial}\partial\left(\log |s|^2\right) = d\partial\left(\log |s|^2\right).

$$

Stokes's theorem now gives

$$

\int_{\Sigma_\varepsilon} \Omega = \int_{\partial \Sigma_\varepsilon} \partial\left(\log|s|^2\right) = - \sum_{i=1}^k \int_{\partial\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon)}\partial\left(\log |s|^2\right).

$$

Hence

$$

\deg(L) = \frac{i}{2\pi}\int_\Sigma \Omega = -\lim_{\varepsilon \to 0} \sum_{i=1}^k \frac{i}{2\pi}\int_{\partial\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon)} \partial\left(\log |s|^2\right).

$$

Consider now one of the discs $\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon)$ and write the corresponding holomorphic coordinate as $z = z^i$. Pick a non-vanishing holomorphic section $\sigma$ of $L$ on $U_i$, and write $s(z)=z^{a_i}f(z)\sigma(z)$, where $f$ is a non-vanishing holomorphic function on $\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon)$. Let $h(z) = |\sigma(z)|^2$, a non-vanishing smooth function. Since $|s|^2$ does not vanish on $\partial\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon)$, we have

$$

\begin{align*}

\partial\left(\log|s|^2\right) &= \frac{\partial\left(z^{a_i}\bar{z}^{a_i}|f(z)|^2h(z)\right)}{z^{a_i}\bar{z}^{a_i}|f(z)|^2h(z)} \\

&= a_i\frac{dz}{z} + u(z)dz,

\end{align*}

$$

where $u$ is a smooth function of $z$ on $\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon)$. Note now that $\partial\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon)$ can be parametrized in $z$-coordinates via $z = \varepsilon e^{i\theta}$ for $\theta \in [0,2\pi]$, so $dz = i\varepsilon e^{i\theta}d\theta$. This gives

$$

\frac{i}{2\pi}\int_{\partial\overline{U}_i(\varepsilon)} \partial\left(\log |s|^2\right) = \frac{i}{2\pi}\int_{0}^{2\pi} a_i id\theta + \frac{i}{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} u(\varepsilon e^{i\theta})i\varepsilon e^{i\theta}d\theta.

$$

The first term is just $-a_i$, and the second term goes to zero as $\varepsilon \to 0$. Applying this to each term in the sum for $\deg(\mathcal{O}(D))$ yields the result.