We’ll be continuing our journey on sheaves and their cohomology today. Last time we ended up in a situation where we considered a short exact sequence of sheaves

\[0 \longrightarrow \mathcal{F} \longrightarrow \mathcal{G} \longrightarrow \mathcal{H} \longrightarrow 0,\]

on a topological space $X$. This gave us a short exact sequence of sections

\[0 \longrightarrow \mathcal{F}(U) \longrightarrow \mathcal{G}(U) \longrightarrow \mathcal{H}(U),\]

for every open set $U \subset X$.

We noted that the map $\mathcal{G}(U) \longrightarrow \mathcal{H}(U)$ needed not to be surjective, which leads us to the question, how “far” is it from being surjective? The cohomology $H^1(U, \mathcal{F})$ turns out to measure exactly this. We are often interested in the case $U =X$ and call the sections global sections. If the group $H^1(X, \mathcal{F})$ is zero, then the exact sequence implies that every global section of $\mathcal{H}$ lifts to a global section of $\mathcal{G}$.

The exactness of the first sequence is a purely local property, whereas the exactness of the second sequence is a global property.

More formally, sheaf cohomology is a theory that is used to compute and understand this defect in exactness via the use of invariants, namely the images under derived functors $R^i\Gamma$ usually written as $H^i(X,-)$.

Last time we went over the example using the exact sequence of sheaves on $\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}$ given by

\[0 \longrightarrow \underline{\Bbb R}\to \Omega^0 \longrightarrow \Omega^1 \longrightarrow 0.\]

We noted that even though this is exact, passing to global sections

\[0 \longrightarrow \underline{\Bbb R}(\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\})\to \Omega^0(\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}) \longrightarrow \Omega^1(\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}),\]

ended up causing an issue with the surjectivity of the last map as the differential form

\[d\theta = \frac{-ydx + xdy}{x^2+y^2} \in \Omega^1(\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}),\]

is closed, but not exact. As mentioned above, this failure of surjectivity is measured by the group $H^1(\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}, \underline{\Bbb R}) = \Bbb R$. What this is saying is that even though every closed form is locally exact (a local property) we cannot expect this to hold globally on all of $\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}$ (a global property).

The way you should be thinking about this is captured by the following quote: “Suppose you have a topological space and a covering for that space such that you can do something you want on each set of the covering. Can you do it on the whole space?”

On any manifold $M$ of dimension $n$, prove that the sequence of sheaves

$$

0 \longrightarrow \underline{\Bbb R}\to \Omega^0 \longrightarrow \Omega^1\longrightarrow \dots \longrightarrow \Omega^n \longrightarrow 0

$$

is exact. Recall that it suffices to prove exactness on stalks.

We’ll begin by quickly going over additive and abelian categories. The motivation for this is that we mainly want to be able to do homological algebra on $\mathbf{Sh}(X)$ like we are able to do in $\mathbf{Ab}$ or $R$-$\textbf{Mod}$.

A category $\mathscr{C}$ is called additive if for every two objects $A, B \in \mathscr{C}$ the Hom-set $\operatorname{Hom}(A,B)$ has an abelian group structure and

- The compositions $\operatorname{Hom}(A_1,A_2) \times \operatorname{Hom}(A_2,A_3) \to \operatorname{Hom}(A_1,A_3)$ given by $(f,g) \mapsto g \circ f$ are bilinear.

- $\mathscr{C}$ has an zero object.

- For any two $A_1,A_2 \in \mathscr{C}$ there exists $B \in \mathscr{C}$ with morphisms $j_i : A_i \to B$ and $p_i : B \to A_i$ which make $B$ the direct sum and the direct product of $A_1$ and $A_2$.

$\mathscr{C}$ having a zero object $0$ means that $0$ is initial and terminal. I.e. for any object $A \in \mathscr{C}$ there exists unique morphisms $A \to 0$ and $0 \to A$.

An additive category $\mathscr{C}$ is called abelian if the following condition holds: Every morphism $f \in \operatorname{Hom}(A,B)$ admits a kernel and a cokernel. Furthermore, we require the map $A/\ker(f) \to \operatorname{im}(f)$ to be an isomorphism.

The above condition pretty much says that for any morphism $f : A \to B$ we have the following diagram:

\[\xymatrix{

\ker(f) \ar@{->}[r]^{i} & A \ar@{->}[d] \ar@{->}[rr]^{f} & & B \ar@{->}[r]^{\pi} & \operatorname{coker}(f). \\

& \operatorname{coker}(i) \ar@{->}[rr]_{\sim} & & \ker(\pi) \ar@{->}[u] &

}\]

In particular, we have the notion of exact sequences in abelian categories.

Consider a commutative ring $R$. The category $R$-$\textbf{Mod}$ of $R$-modules is abelian.

Let $X$ be a topological space. The category of sheaves of abelian groups $\textbf{Sh}(X)$ is abelian.

For a scheme $X$, the categories $\textbf{Coh}(X)$ and $\textbf{Qcoh}(X)$ of coherent and quasi-coherent sheaves on $X$ are also both abelian.

These conditions let us adapt the ideas used in homological algebra for modules to any abelian category. This means we can apply important concepts like exactness, complexes, chain homotopies, and cohomology objects more broadly. Plus, well-known theorems, such as the snake lemma, can be extended to this wider context too.

Actually, for many purposes, it’s enough to understand homological algebra through modules. This idea is rooted in the Freyd-Mitchell embedding theorem. This theorem states that for any small abelian category, there’s a corresponding commutative ring $R$ and a full, faithful, and exact functor to $R$-$\textbf{Mod}$. As a result, using something like diagram-chasing as a proof method is perfectly valid, even in categories that don’t inherently incorporate this concept.

Another technical tool we need is that of resolutions. More specifically injective resolutions.

An object $I$ in an abelian category is said to be injective if, for every monomorphism $f : A \to B$ and every morphism $g : A \to I$, there exists a morphism $h : B \to I$ extending $g$ to $B$, i.e. the following diagram commutes:

$$

\xymatrix{

A \ar@{->}[d]_{f} \ar@{->}[r]^{g} & I \\

B \ar@{-->}[ru]_{h} &

}.

$$

For example, the injective objects in $\textbf{Ab}$ are the divisible groups .

A complex $(A^\bullet, d^\bullet)$ in an abelian category is a sequence of objects $A^i$ and maps $d^i : A^i \to A^{i+1}$ such that $d^{i+1} \circ d^i = 0$. A morphism of complexes $f : (A^\bullet, d^\bullet_{A}) \to (B^\bullet, d^\bullet_{B})$ is a collection of morphisms $f^i : A^i \to B^i$ such that $d^i_{B}\circ f^{i}=f^{i-1}\circ d^i_{A}$.

The degree $i$ cohomology of a complex $(A^\bullet, d^\bullet)$ is the object

$$

H^i(A^\bullet) = \operatorname{coker}(\operatorname{im}(d^{i-1}) \to \ker(d^i)).

$$

For every $i$, a morphism of complexes $f : (A^\bullet, d^\bullet_{A}) \to (B^\bullet, d^\bullet_{B})$ induces morphisms $H^i(f) : H^i(A^\bullet) \to H^i(B^\bullet)$. A morphism $f$ of complexes is called a quasi-isomorphism if the induced morphisms $H^i(f)$ are isomorphisms for every $i$.

A complex $(B^\bullet, d^\bullet)$ is called a resolution of an object $A$ if $\operatorname{im}(d^i) = \ker(d^{i+1})$ for $i \ge 0$ and there exists an injective morphism $\epsilon : A \to B^0$ such that the sequence

$$

0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow B^0 \longrightarrow B^1 \longrightarrow \dots

$$

is exact.

We say that the abelian category $\mathscr{C}$ has enough injective objects if every object $A$ of $\mathscr{C}$, there exists a monomorphism from $A$ to an injective object.

If $\mathscr{C}$ has enough injectives, then every object of $\mathscr{C}$ admits an injective resolution, i.e. a resolution by a complex $I^\bullet$ all of whose objects are injective objects.

Let $A \in \mathscr{C}$. Since $\mathscr{C}$ has enough injectives, there exists an injective object $I^0$ such that $\epsilon : A \hookrightarrow I^0$. Similarly, there exists an injective object $I^1$ such that $\operatorname{coker}(\epsilon) \hookrightarrow I^1$. We can now define $d^0 : I^0 \to I^1$ as the composition of $\operatorname{coker}(\epsilon) \hookrightarrow I^1$ with the natural map $I^0 \to \operatorname{coker}(\epsilon)$. Rinse and repeat to define $d^k : I^k \to I^{k+1}$.

Now, here is the key lemma that is going to be of utmost importance.

Let $0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow I^\bullet$ be any resolution of an object $A$ and $0 \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow J^\bullet$ an injective resolution of $B$. Then any morphism $f : A \to B$ induces a morphism of complexes $f^\bullet : I^\bullet \to J^\bullet$ that is unique up to homotopy.

This implies that any two injective resolutions $0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow I^\bullet$ and $0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow J^\bullet$ of the same object $A$ are homotopy equivalent, thus it holds also for the complexes $F(I^\bullet)$ and $F(J^\bullet)$, which guarantees that

\[H^i(F(I^\bullet)) \cong H^i(F(J^\bullet))\]

for every $i$.

We need a few more lemmas for the main result, the first of which I’m going to present here without proof. The proof is quite technical but follows from some rather elementary homological algebra. See for example “Methods of Homological Algebra” by Manin and Gelfand.

Let $\mathscr{C}$ be an abelian category with enough injectives. If

$$

0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow C \longrightarrow 0

$$

is an exact sequence in $\mathscr{C}$, then there exist injective resolutions $I^\bullet, J^\bullet$ and $K^\bullet$ of $A, B$, and $C$ respectively, that fit into a commutative diagram with exact rows:

$$

\xymatrix{

& 0 \ar@{->}[d] & 0 \ar@{->}[d] & 0 \ar@{->}[d] & \\

0 \ar@{->}[r] & A \ar@{->}[r] \ar@{->}[d] & B \ar@{->}[r] \ar@{->}[d] & C \ar@{->}[r] \ar@{->}[d] & 0 \\

0 \ar@{->}[r] & I^\bullet \ar@{->}[r] & J^\bullet \ar@{->}[r] & K^\bullet \ar@{->}[r] & 0.

}

$$

If $F : \mathscr{C} \to \mathscr{D}$ is a left-exact functor between abelian categories and

$$

0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow B \xrightarrow{~~\varphi~~} C \longrightarrow 0

$$

is a split exact sequence in $\mathscr{A}$, then

$$

0 \longrightarrow F(A) \longrightarrow F(B) \xrightarrow{~~F(\varphi)~~} F(C) \longrightarrow 0

$$

is exact and splits in $\mathscr{D}$.

The sequence is exact since $F$ is left-exact. If $\psi$ is a section of $\varphi$, the morphism $F(\psi): F(C) \to F(B)$ is a section of $F(\varphi)$ which concludes the proof.

One last thing we are going to need is the following.

If $ 0 \longrightarrow A \xrightarrow{~~i~~} B \longrightarrow C \longrightarrow 0$ is a short exact sequence in an abelian category with $A$ injective. Then the sequence splits.

Note that the map $i: A \to B$ is a monomorphism. Since $A$ is injective there exists a map $h : B \to A$ such that the following diagram commutes:

$$

\xymatrix{

A \ar@{->}[d]_{i} \ar@{->}[r]^{\operatorname{id}} & A \\

B \ar@{-->}[ru]_{h} &

}.

$$

Thus $i \circ h$ is a retract and so the splitting lemma yields the result.

The “motivation” for what’s coming next should be this. We start off with a left-exact functor $F : \mathscr{C} \to \mathscr{D}$ of abelian categories and a short exact sequence

\[0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow C \longrightarrow 0.\]

Applying $F$ we obtain

\[0 \longrightarrow F(A) \longrightarrow F(B) \longrightarrow F(C).\]

Now what we would want to do is to measure the extent to which $F$ fails to be exact by extending the above to a long exact sequence

\[0 \longrightarrow F(A) \longrightarrow F(B) \longrightarrow F(C) \longrightarrow R^1F(A) \longrightarrow R^1F(B) \longrightarrow R^1F(C) \longrightarrow \dots\]

To understand what I mean by failure of $F$ being exact, note that if $R^1F(A) = 0$, then $F$ is exact. So $R^1F(A)$, in a sense measures the exactness of $F$. We know from our background in homological algebra that if we have a short exact sequence of cochain complexes

\[0 \longrightarrow F(I^\bullet) \longrightarrow F(J^\bullet) \longrightarrow F(K^\bullet) \longrightarrow 0,\]

we obtain an induced long exact sequence in cohomology

\[0 \longrightarrow H^0(F(I^\bullet)) \longrightarrow H^0(F(J^\bullet)) \longrightarrow H^0(F(K^\bullet)) \longrightarrow H^1(F(I^\bullet)) \longrightarrow \dots\]

This motivates the following idea. Maybe, for each of the objects $A, B$ and $C$ we can associate a cochain complex and then define the right-derived functors $R^iF$ of $F$ in terms of the cohomology of these cochain complexes. This is exactly the kind of thing we’ve just developed the theory for.

Let $\mathscr{C}$ and $\mathscr{D}$ be two abelian categories, and $F$ a left-exact functor from $\mathscr{C}$ to $\mathscr{D}$. Suppose in addition that $\mathscr{C}$ has enough injectives.

For every $A \in \mathscr{C}$, there exists objects $R^iF(A) \in \mathscr{D}$, determined up to isomorphism, satisfying the following conditions.

- $R^0F(A) = F(A)$.

-

For every short exact sequence

$$

0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow C \longrightarrow 0

$$

in $\mathscr{C}$, we can construct a long exact sequence

$$

0 \longrightarrow F(A) \longrightarrow F(B) \longrightarrow F(C) \longrightarrow R^1F(A) \longrightarrow R^1F(B) \longrightarrow R^1F(C) \longrightarrow \dots,

$$

in $\mathscr{D}$.

- For every injective object $I \in \mathscr{C}$, $R^iF(I) = 0$ for all $i > 0$.

For every $A \in \mathscr{C}$, choose an injective resolution $I^\bullet$ of $A$. Using this we obtain a complex $F(I^\bullet)$ in $\mathscr{D}$. Define then

$$

R^iF(A) = H^i(F(I^\bullet)).

$$

To see that $R^0F(A) = F(A)$, note that since $F$ is left-exact, the sequence

$$

0 \longrightarrow F(A) \longrightarrow F(I^0) \longrightarrow F(I^1)

$$

is exact. It follows that

$$

\begin{align*}

R^0F(A) &= H^0(F(I^\bullet)) \\

&= \ker(F(d^0) : F(I^0) \to F(I^1)) \\

&= F(A).

\end{align*}

$$

Also, $R^iF(A)$ does not depend, up to isomorphism, on the choice of the resolution due to the resolutions being unique up to homotopy.

Now, let

$$

0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow C \longrightarrow 0

$$

be a short exact sequence in $\mathscr{C}$. The horseshoe lemma implies that there exists injective resolutions $I^\bullet, J^\bullet$ and $K^\bullet$ of $A, B$ and $C$ respectively such that

$$

0 \longrightarrow I^\bullet \longrightarrow J^\bullet \longrightarrow K^\bullet \longrightarrow 0

$$

is a short exact sequence of complexes. Since every short exact sequence of injective objects is split we obtain a short exact sequence

$$

0 \longrightarrow F(I^\bullet) \longrightarrow F(J^\bullet) \longrightarrow F(K^\bullet) \longrightarrow 0

$$

after applying $F$. Since such an exact sequence of complexes gives a long exact sequence of cohomology the result follows along with the fact that $R^0F = F$.

To see the last point, note that if $I$ is injective we can consider the injective resolution $0 \longrightarrow I \longrightarrow I \longrightarrow 0$, which gives $0 \longrightarrow F(I) \longrightarrow 0$ so $R^iF(I) = 0$ for $i > 0$.

Note that if $F$ is an exact functor, then $R^iF(A) = 0$ for any object $A$ and $i > 0$. If

\[0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow I^0 \longrightarrow I^1 \longrightarrow \dots\]

is an injective resolution, then the complex $F(I^\bullet)$ is exact in degrees $i > 0$. Hence $R^iF(A) = H^i(F(I^\bullet)) = 0$ for $i > 0$.

While we defined right-derived functors using injective resolutions, these can be computationally cumbersome. Fortunately, they can also be calculated using more flexible classes of resolutions, simplifying practical applications.

Given a functor $F$ between abelian categories $\mathscr{C}$ and $\mathscr{D}$, with $\mathscr{D}$ having enough injectives, we call an object $A \in \mathscr{C}$ $F$-acyclic if $R^iF(A) = 0$ for $i > 0$.

In particular, this implies that if

\[0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow C \longrightarrow 0\]

is exact and $A$ is $F$-acyclic, then

\[0 \longrightarrow F(A) \longrightarrow F(B) \longrightarrow F(C) \longrightarrow 0\]

is exact.

If $0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow J^\bullet$ is an $F$-acyclic resolution of $A$, then there exists a natural isomorphism $R^iF(A) = H^i(F(J^\bullet))$. In other words, cohomology can be computed using acyclic objects.

The proof here is essentially done by dimension shifting and inducting on $i$. We obtain a short exact sequence

$$

0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow J^0 \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow 0

$$

where $B$ is the cokernel of $d^0$. Now $B$ admits the shifted resolution

$$

0 \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow J^1 \longrightarrow J^2 \longrightarrow \dots

$$

The sequence $0 \longrightarrow A \longrightarrow J^0 \longrightarrow B \longrightarrow 0$ induces a long exact sequence of derived objects and as $J^0$ is acyclic, this long exact sequence can be summarized by

$$

\begin{align*}

R^{i}F(B) &= R^{i+1}F(A) \quad \text{for } i \ge 1, \\

R^1F(A) &= \operatorname{coker}(F(J^0) \to F(B)).

\end{align*}

$$

The first equality yields by induction that

$$

\begin{align*}

R^iF(A) &= R^{i-1}F(B) \\

&= H^{i-1}(F(J_1^\bullet)) \\

&=H^{i}(F(J^\bullet))

\end{align*}

$$

where $J_1^\bullet$ denotes the complex with $J^0$ excluded.

The left-exactness of $F$ implies that $F(B) = \ker(F(J^1) \to F(J^2))$, and the second equality above is exactly $R^1F(A) = H^1(F(J^\bullet))$.

The category in which we are going to develop this theory is that of $\mathcal{O}_X$-modules, where $\mathcal{O}_X$ is a sheaf of rings on $X$. This category is abelian and has enough injectives. Moreover, this includes sheaves of abelian groups as a special case.

Let’s recall first how a ringed space and morphisms between ringed spaces are defined.

A ringed space $(X, \mathcal{O}_X)$ is a pair, where $X$ is a topological space and $\mathcal{O}_X$ a sheaf of commutative rings with unity on $X$.

A morphism between two ringed spaces $(X, \mathcal{O}_X)$ and $(Y, \mathcal{O}_Y)$ is a pair $(f,f^\sharp)$ where $f : X \to Y$ is a continuous map, and $f^\sharp : \mathcal{O}_Y \to f_\ast\mathcal{O}_X$ is a morphism of sheaves of rings.

Here are a few examples of ringed spaces.

Topological spaces with the sheaves of continuous real-valued functions.

Smooth manifolds with the sheaves of $C^\infty$ functions.

Complex manifolds with the sheaves of holomorphic functions.

Schemes with the sheaves of regular functions.

Let $(X, \mathcal{O}_X)$ be a ringed space. A

sheaf of $\mathcal{O}_X$-modules is a sheaf $\mathcal{F}$ on $X$ satisfying the following properties.

-

For each open set $U \subset X$, the group $\mathcal{F}(U)$ is an $\mathcal{O}_X(U)$-module.

-

For every inclusion of open sets $V \hookrightarrow U$, the restriction map $\rho_{U,V} : \mathcal{F}(U) \to \mathcal{F}(V)$ is compatible with the module structures. That is, for $s \in \mathcal{O}_X(U)$ and $t \in \mathcal{F}(U)$, we have that $\rho_{U,V}(st) = \rho_{U,V}(s)\rho_{U,V}(t)$.

To get the idea, consider $(M, C^\infty_M)$ where $M$ is a smooth manifold. The sheaf of sections of the tangent bundle $\Gamma$ has a natural $C^\infty_M$-module structure.

Given a ringed space $(X, \mathcal{O}_X)$, denote the cateogry of $\mathcal{O}_X$-modules by $\mathcal{O}_X$-$\textbf{Mod}$. It’s not too difficult to see that if, $\mathcal{F}$ is an $\mathcal{O}_X$-module, then $f_\ast \mathcal{F}$ has a natural $f_\ast\mathcal{O}_X$-module structure. The morphism $f^\sharp : \mathcal{O}_Y \to f_\ast \mathcal{O}_X$ then gives $f_\ast \mathcal{F}$ a natural $\mathcal{O}_Y$-module structure.

On the other hand, for an $\mathcal{O}_Y$-module $\mathcal{G}$, the inverse image $f^{-1}\mathcal{G}$ is an $f^{-1}\mathcal{O}_Y$-module, but not an $\mathcal{O}_X$-module. However, $\mathcal{O}_X$ does have an $f^{-1}\mathcal{O}_Y$-module structure, obtained using the fact that $f^{-1}$ and $f_\ast$ form an adjoint pair. Indeed, we have a morphism $f^\sharp : \mathcal{O}_Y \to f_\ast\mathcal{O}_X$ which by adjunction yields a morphism $f^{-1}\mathcal{O}_Y \to \mathcal{O}_X$. Using this $\mathcal{O}_X$ can be viewed as an $f^{-1}\mathcal{O}_Y$-module by “restriction of scalars” and then by “extension of scalars”, one can make $f^{-1}\mathcal{G}$ into an $\mathcal{O}_X$-module by defining

\[f^\ast\mathcal{G} = f^{-1}\mathcal{G}\otimes_{f^{-1}\mathcal{O}_Y} \mathcal{O}_X.\]

The adjunction

\[\operatorname{Hom}(f^{-1}\mathcal{G}, \mathcal{F}) = \operatorname{Hom}(\mathcal{G}, f_\ast\mathcal{F})\]

extends to

\[\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}(f^{\ast}\mathcal{G}, \mathcal{F}) = \operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_Y}(\mathcal{G}, f_\ast\mathcal{F})\]

via the tensor-hom adjunction.

As we are eventually going to define sheaf cohomology as the derived functors of the global section functor we ought to verify that the category $\mathcal{O}_X$-$\textbf{Mod}$ has enough injectives.

The category $\mathcal{O}_X$-$\textbf{Mod}$ has enough injectives.

Let $\mathcal{F}$ be an $\mathcal{O}_X$-module. For each $x \in X$ there exists an immersion $i_x : \mathcal{F}_x \to I_x$ of the stalk $\mathcal{F}_x$ into an injective $\mathcal{O}_{X,x}$-module $I_x$. Let $j: \{x\} \to X$ be the inclusion of the one-point space and define

$$

I = \prod_{x \in X} j_{\ast}(I_x).

$$

Consider now $(\{x\}, \mathcal{O}_{X,x})$ as an ringed space. Adjunction yields that

$$

\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}(\mathcal{F}, j_\ast I_x) = \operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_{X,x}}(\mathcal{F}_x, I_x).

$$

To see that $I$ is injective, note that

$$

\begin{align*}

\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}(\mathcal{F}, I) &= \operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}\left(\mathcal{F}, \prod_{x \in X} j_{\ast}(I_x)\right) \\

&=\prod_{x \in X}\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}\left(\mathcal{F}, j_{\ast}(I_x)\right) \\

&=\prod_{x \in X}\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_{X,x}}\left(\mathcal{F}_x, I_x\right).

\end{align*}

$$

Since the functor from $\mathcal{O}_X$-$\textbf{Mod}$ to $\mathcal{O}_{X,x}$-$\textbf{Mod}$ is exact and $\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_{X,x}}\left(-, I_x\right)$ is exact due to the injectivity of $I_x$, the functor $\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}(-, I)$ is exact, i.e. $I$ is an injective $\mathcal{O}_X$-module.

Considering the global sections functor $\Gamma$ as a functor from $\mathcal{O}_X$-$\textbf{Mod}$ to $\Gamma(X,\mathcal{O}_X)$-$\textbf{Mod}$ we end up with the following definition.

The sheaf cohomology groups are the right-derived functors of the global section functor. If $\mathcal{F}$ is an $\mathcal{O}_X$-module, we denote

$$

H^i(X,\mathcal{F}) = R^i\Gamma(\mathcal{F}).

$$

Just as we have seen before, a short exact sequence of $\mathcal{O}_X$-modules induces a long exact sequence of cohomology.

Injective resolutions are hard to come by in sheaf theory, however, since we can compute cohomology using acyclic resolutions, finding some simpler classes of sheaves would be useful for us. Fortunately,

there is a class of sheaves known as flasque sheaves (due to Godement) which are $\Gamma$-acyclic, and every sheaf has a resolution by flasque sheaves.

A sheaf $\mathcal{F}$ of $\mathcal{O}_X$-modules is flasque if for every inclusion of open sets $V \subset U$, the restriction morphism

$\mathcal{F}(U) \to \mathcal{F}(V)$ is surjective.

Skyscraper sheaves are flasque.

For a sheaf $\mathcal{F}$, the sheaf of all sections of the étale space, continuous or not, is flasque.

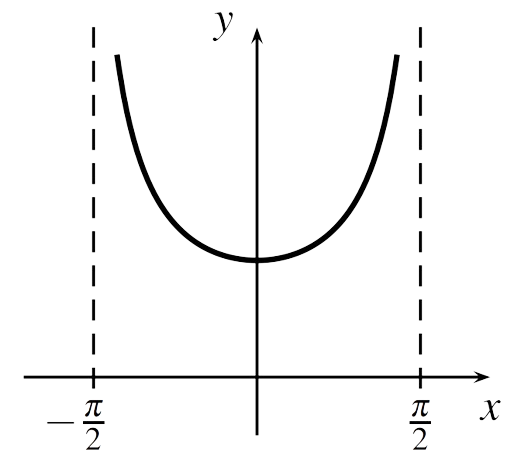

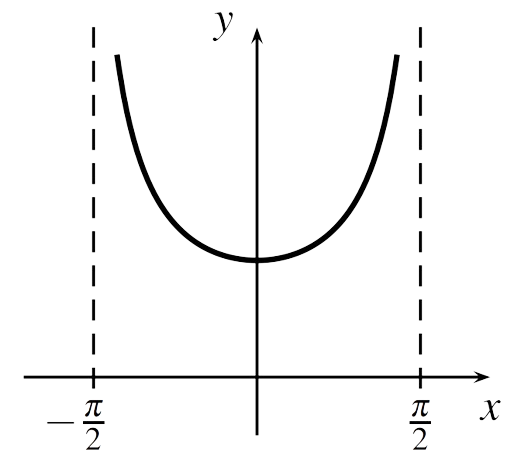

Consider the continuous map $\sec : (-\pi/2, \pi/2) \to \Bbb R$. This map blows up at the endpoints $-\pi/2$ and $\pi/2$ which means that it cannot be extended to a continuous function on all of $\Bbb R$. It follows that the sheaf of continuous functions on $\Bbb R$ is not flasque since $C^\infty(\Bbb R) \to C^\infty((-\pi/2,\pi/2))$ is not surjective.

Every injective $\mathcal{O}_X$-module is flasque.

For an open set $U \subset X$, let $j : U \hookrightarrow X$ be the inclusion map and consider the $\mathcal{O}_X$-module $j_!(\mathcal{O}_X)$ where $j_!$ is extension by zero of $\mathcal{O}_U$ along $j$. Suppose that $\mathcal{F}$ is an injective $\mathcal{O}_X$-module and $V \subset U \subset X$ open sets. Then there is an injective morphism $j_!(\mathcal{O}_V) \hookrightarrow j_!(\mathcal{O}_U)$. Applying the contravariant functor $\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}(-, \mathcal{F})$ to this the inclusion $j_!(\mathcal{O}_V) \hookrightarrow j_!(\mathcal{O}_U)$ yields a surjection

$$

\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}( j_!(\mathcal{O}_U), \mathcal{F}) \to \operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}( j_!(\mathcal{O}_V), \mathcal{F}).

$$

Since $j_!$ and $j^\ast$ form an adjoint pair this yields an isomorphism

$$

\operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}( j_!(\mathcal{O}_U), \mathcal{F}) \cong \operatorname{Hom}_{\mathcal{O}_X}( \mathcal{O}_U, j^\ast\mathcal{F}) = \mathcal{F}(U)

$$

and likewise for $V$. We obtain a surjection $\mathcal{F}(U) \to \mathcal{F}(V)$, i.e. $\mathcal{F}$ is flasque.

Taking $\mathcal{O}_X = \underline{\Bbb Z}$ the above proposition yields that injective sheaves of abelian groups are flasque.

Flasque sheaves of $\mathcal{O}_X$-modules are acyclic for sheaf cohomology.

Let $\mathcal{F}$ be a flasque $\mathcal{O}_X$-module and embed it into an injective $\mathcal{O}_X$-module $I$. The quotient $\mathcal{Q} = I/\mathcal{F}$ is flasque. Passing to cohomology and using the fact that $I$ is acyclic we get

$$

0 \longrightarrow \mathcal{F}(X) \longrightarrow I(X) \longrightarrow \mathcal{Q}(X) \longrightarrow H^1(X,\mathcal{F}) \longrightarrow 0

$$

and

$$

0 \longrightarrow H^i(X, \mathcal{Q}) \longrightarrow H^{i+1}(X,\mathcal{F}) \longrightarrow 0, \quad i \ge 2.

$$

Since $0 \longrightarrow \mathcal{F}(X) \longrightarrow I(X) \longrightarrow \mathcal{Q}(X) \longrightarrow 0$ is exact, $H^1(X,\mathcal{F}) = 0$ and since $\mathcal{Q}$ is flasque the proof follows by induction on $i$.

Yet another interesting class of sheaves is that of fine sheaves. Before we define these we need to define partitions of unity for sheaves.

Let $\mathcal{U} = \{U_i\}_{i\in I}$ be a locally finite cover of $X$ and $\mathcal{F}$ a sheaf on $X$. A partition of unity for $\mathcal{F}$ subordinate to $\mathcal{U}$ is a collection of morphisms of sheaves $\{\eta_i : \mathcal{F} \to \mathcal{F}\}_{i \in I}$ such that for each $i \in I$

$$

\operatorname{supp}(\eta_i) := \overline{\{x \in X \mid \eta_{i,x} \ne 0\}} \subset U_i,

$$

and for all $x \in X$, $\sum_{i\in I} \eta_{i,x} = \operatorname{id}_{\mathcal{F}_x}, $where $\eta_{i,x} : \mathcal{F}_x \to \mathcal{F}_x$ is the map on stalks.

A sheaf $\mathcal{F}$ on a topological space $X$ is fine if it admits partitions of unity subordinate to any locally finite cover of $X$.

The most important property of a fine sheaf is that it is acyclic on sufficiently nice spaces.

Let $\mathcal{R}$ be a fine sheaf of rings on a paracompact space $X$ and let $\mathcal{F}$ be a sheaf of $\mathcal{R}$-modules. Then $\mathcal{F}$ is acyclic.

The above theorem implies that the class of fine sheaves is suited very well for studying manifolds. The rest of this post will develop on this idea and its implications on de Rham cohomology.

Let $X$ be a smooth $n$-manifold with tangent bundle $\pi : TX \to X$ and denote by $\Omega^k_X := \Gamma\left(-, \Lambda^k T^\ast X\right)$ the sheaf of $k$-forms. By convention $\Omega^0_X = \mathcal{O}_X$ is the structure sheaf on $X$, i.e. the sheaf of continuous functions.

Sheaves of modules over a fine sheaf of rings are fine.

Let $(X, \mathcal{O}_X)$ be a ringed space and suppose that $\mathcal{U} = \{U_i\}_{i\in I}$ is a locally finite cover of $X$ and $\mathcal{O}_X$ admits a partition of unity $\{s_i \in \mathcal{O}_X(X)\}_{i \in I}$ subordinate to $\mathcal{U}$. Let $\mathcal{F}$ be an $\mathcal{O}_X$-module. The maps

$$

\begin{align*}

\eta_{i,U} : \mathcal{F}(U) &\to \mathcal{F}(U) \\

\sigma &\longmapsto s_i\vert_{U} \cdot \sigma

\end{align*}

$$

assemble to a partition of unity $\{\eta_i : \mathcal{F} \to \mathcal{F} \}$ for $\mathcal{F}$ subordinate to $\mathcal{U}$.

For each $k \ge 0$, $\Omega^k_X$ is a fine sheaf. In particular, $\Omega^k_X$ is acyclic.

Since $\mathcal{O}_X$ is a fine sheaf on $X$, and since each $\Omega^k_X$ is an $\mathcal{O}_X$-module, the first assertation follows from the proposition above and the second follows since fine sheaves on $X$ are acyclic.

The sheaf cohomology of $\Omega^\bullet_X$ is called the de Rham cohomology of $X$, written

$$

H^i_{dR}(X) := H^i(\Gamma(X, \Omega^\bullet_X)).

$$

For a smooth manifold $X$, the complex of sheaves

$$

0 \longrightarrow \underline{\Bbb R} \longrightarrow \Omega^0_X \longrightarrow \Omega^1_X \longrightarrow \dots

$$

is acyclic, where $\underline{\Bbb R}$ denotes the constant sheaf on $X$ with stalks $\Bbb R$.

This is the exercise I left for you in the beginning and I highly suggest doing this the nuts and bolts way. Anyway, it suffices to compute this on stalks, where for each $x \in X$ we have a coordinate chart $U \cong \Bbb R^n$. The Poincaré lemma implies that $H^i_{dR}(U) = 0$ for all $i > 0$. Since direct limits commute with cohomology this yields

$$

\begin{align*}

H^i(X, \Omega^\bullet_{X,x}) &= \varinjlim_{U \ni x} H^i(U, \Omega^\bullet_{X}) \\

&= \varinjlim_{U \ni x} H^i_{dR}(U) \\

&= 0.

\end{align*}

$$

For a smooth manifold $X$, there is an isomorphism

$$

H^\bullet_{dR}(X) \cong H^\bullet(X,\underline{\Bbb R})

$$

where $\underline{\Bbb R}$ is the constant sheaf.

To prove the de Rham theorem we are going to need the following theorem which I’m not going to prove here.

Let $X$ be a topological space, $A$ an abelian group, and $\underline{A}$ the constant sheaf on $X$ with stalks $A$. Then

$$

H^i(X,\underline{A}) \cong H^i(X, A).

$$

where $H^i(X,A)$ denotes the ordinary cohomology of $X$ with coefficients in $A$.

The de Rham theorem follows now follow from the two results above.

For a smooth manifold $X$, there is an isomorphism between de Rham cohomology and singular cohomology:

$$

H^\bullet_{dR}(X) \cong H^\bullet(X,\Bbb R).

$$

To end this, let’s prove that for a smooth, compact manifold $X$, the groups $H^i_{dR}(X)$ are finite-dimensional. This is going to need you to know some Riemannian geometry and a bit about Čech cohomology.

For a smooth, compact manifold $X$, the groups $H^i_{dR}(X)$ are finite-dimensional for all $i \ge 0$.

Equip $X$ with a Riemannian metric. Then, every point in $X$ admits a geodesically convex neighborhood, meaning any two points in the neighborhood lie on a geodesic that is contained in the neighborhood. The compactness of $X$ allows us to choose a finite cover $\mathcal{U} = \{U_1,\dots, U_k\}$ consisting of geodesically convex open sets. Since for any choice of indices $i_1,\dots,i_m \in \{1,\dots,k\}$, the intersection $U_{i_1,\dots, i_k} = U_{i_1}\cap \dots \cap U_{i_k}$ is also geodesically convex and such as set has vanishing de Rham cohomology, the de Rham theorem yields that

$$

H^i(U_{i_1,\dots,i_k}, \underline{\Bbb R}\vert_{U_{i_1,\dots,i_k}}) \cong H^{i}_{dR}(U_{i_1,\dots,i_k}) = 0

$$

for all $i > 0$. It follows that $\underline{\Bbb R}$ is acyclic for the cover $\mathcal{U}$. Leray's theorem yields that $H^i(X,\underline{\Bbb R}) = \check{H}(\mathcal{U}, \underline{\Bbb R})$, and since each $C^i(\mathcal{U}, \underline{\Bbb R})$ in the Čech complex is a finite product of one-dimensional vector spaces, its cohomology thus consists of finite-dimensional vector spaces.