Sheaves

I was planning on writing about derived functors and sheaf cohomology, but I figured that since I had no posts regarding sheaves nor category theory I’ll begin with talking about sheaves and go along from there. This posts assumes some elementary knowledge about category theory.

So what are sheaves and why should you care? Let’s go over some history first.

During his captivity as a prisoner in Austria during World War II, Jean Leray hid his expertise in analysis by presenting himself as an algebraic topologist, a ruse designed to avoid contributing to the Nazi war effort. The concepts he developed during this period would later become crucial, and in some instances, absolutely vital to the advancement of algebraic topology, as well as complex and algebraic geometry. Among his contributions was the introduction of sheaves and the foundational principles of sheaf cohomology.

Typically, the development of any geometric space is a two-step process. Initially you specify a topological space and following that, a particular set of functions is established to provide the space with it’s unique structure. Take, for example, the various types of manifolds—differentiable, smooth, complex, or topological. Each type begins with the foundation of a second countable Hausdorff topological space. What distinguishes one from another are the specific functions applied within the space (smooth, holomorphic, continuous).

The tool to manage such functions is called a sheaf. If you have background in differential geometry you might have crossed paths with something called partitions of unity that allowed you to consider relationships between local and global datum. Well sheaves sorta provide us a framework for solving these types of problems in more general sense.

To understand sheaves we need to begin with something called a presheaf. A presheaf on a topological space $X$ with values in a category $\mathcal{C}$ is a contravariant functor defined on the category of the open subsets of $X$ with values in $\mathcal{C}$. Instead of focusing on this general case we will consider sheaves of abelian groups.

We call the elements of the groups $\mathcal{F}(U)$ sections1 and often write $\rho_{U,V}(s)$ as just $s\vert_V$. Before we define sheaves let’s look at some examples of presheaves.

Now a sheaf is a presheaf, but with some additional conditions.

- (Locality) If $s,t \in \mathcal{F}(U)$ are such that $s\vert_{U_\alpha} = t\vert_{U_\alpha}$ for all $\alpha$, then $s = t$.

- (Gluing) For each $\alpha$ consider sections $s_\alpha \in \mathcal{F}(U_\alpha)$ such that $$ s_\alpha\vert_{U_\alpha \cap U_\beta} = s_\beta\vert_{U_\alpha \cap U_\beta} $$ for each $U_\alpha$ and $U_\beta$. Then there exists $s \in U$ such that $s\vert_{U_\alpha} = s_\alpha$.

The first condition states that if you have two sections $s$ and $t$ of the sheaf $\mathcal{F}$ over the open set $U$ and these sections agree on every part of a covering of $U$ by open sets $U_\alpha$, then $s$ and $t$ must be the same section over $U$. In other words, if locally (on each $U_\alpha$) the sections cannot be distinguished from each other, then they are globally the same on $U$.

The second condition is about the ability to glue local sections to form a global section. If for each pair of indices $\alpha$ and $\beta$, the restrictions of $s_\alpha$ to $U_\alpha \cap U_\beta$ agree with the restrictions of $s_\beta$ to $U_\alpha \cap U_\beta$, then there must exist a global section $s$ over $U$ which, when restricted to each $U_\alpha$, gives you $s_\alpha$. This ensures that local pieces of information (the sections over the smaller open sets $U_\alpha$) can be coherently combined to form a global piece of information (a section over the entire set $U$).

We can fix the problem in above by the following which turns out to be an important2 example.

Okay this is getting quite long already, but I want to cover stalks and morphisms of sheaves before I wrap this up so bear with me.

So let’s begin with stalks. Again we draw intuition from the theory of smooth manifolds. In the context of smooth manifolds, consider $M$ to be such a manifold. We can define a sheaf over $M$ by mapping each open subset $U$ in $M$ to the group $C^\infty(U)$, which consists of all smooth real-valued functions defined on $U$. This sheaf encapsulates the local behavior of smooth functions across $M$. We know that the local properties of $C^\infty$ functions at a specific point are captured by the germs of the functions at that point. Analogously, in the framework of sheaves, these local properties are examined via the stalk of the presheaf at a point, which accumulates all germs of sections that are defined in neighborhoods of that point.

Another even more elementary example of this phenomena is differentiation. If one wants to differentiate a function, it does not suffice to know it’s value at a point, but it suffices to know it’s values in any neighborhood of that point, or said differently it’s value at the level of stalks.

There are two ways to define stalks or maybe one, but some audiences may prefer different presentations so I’m going to give you both.

It’s quite common to denote the elements of $\mathcal{F}_x$ bit abusively as either $(s,U)$ or $[s]_x$.

Now the categorically inclined may notice that some “limiting” process is happening behind the scenes here, and you would be correct. Indeed the stalk of $\mathcal{F}$ at $x \in X$ is the direct limit

\[\mathcal{F}_{x}=\varinjlim _{U\ni x}{\mathcal {F}}(U).\]Let’s take a moment to understand the relationship between sections and stalks. Consider a topological space $X$ and the sheaf $\mathcal{F}$ of smooth functions. For an open set $U \subset X$, if $f \in \mathcal{F}(U)$ is a section, then as a function $f$ is just a choice of a value $f(x) \in \Bbb R$ for each $x \in X$, subject to a local “smooth” condition. Adopting a different perspective, we could think of $f$ as a sequence of germs. At every point $x$, the germ $[f]_x \in \mathcal{F}_x$ gives us the value $f(x)$, but the germ $[f]_x$ contains even more data. For example, we can compute $f’(x)$ from $[f]_x$ alone. Nonetheless we can think of $f$ as a choice of germ $[f]_x \in \mathcal{F}_X$ at each point $x$. This means that we can replace the notion of the value $f(x)$ with $[f]_x$ and this turns out to be useful as for a general sheaf $\mathcal{F}$, the notion of $f(x)$ is not defined, but $[f]_x$ is.

Note now that if $X$ is any topological space and $\mathcal{F}$ any sheaf, for $U \subset X$ and any $x \in U$, we have a natural map

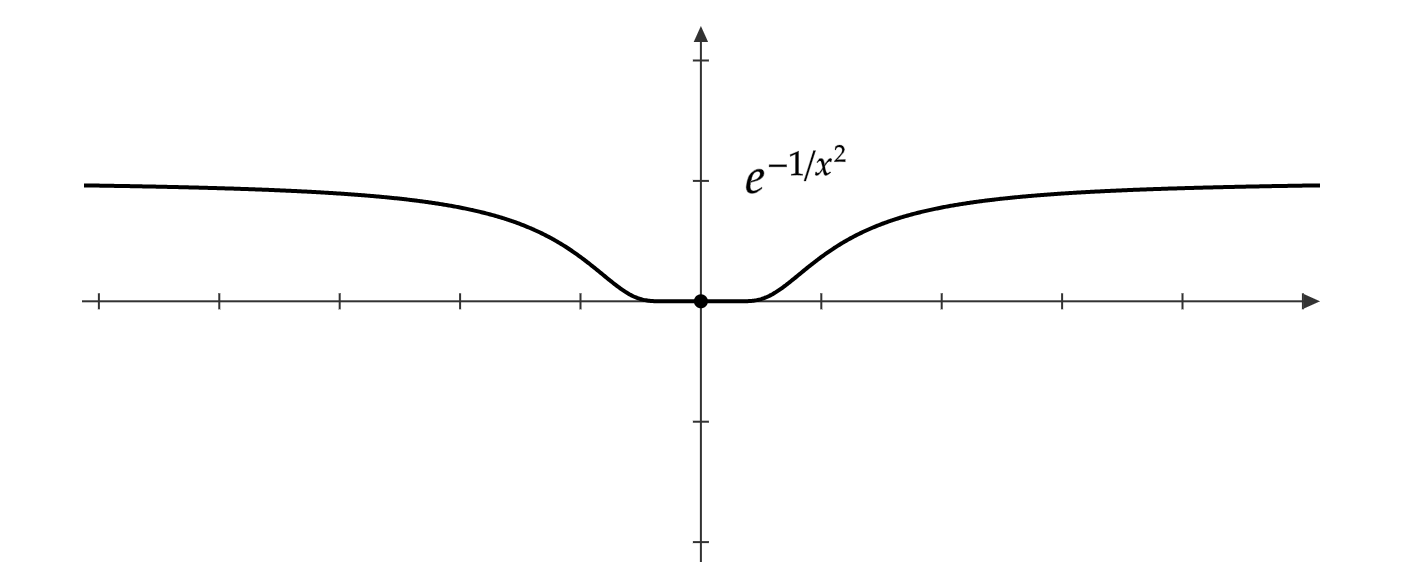

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{F}(U) &\to \mathcal{F}_x \\ s &\mapsto [s]_x, \end{align*}\]taking a section to its local expansion in a neighborhood around $x$. Now clearly this map isn’t injective in general. If it was, $s$ would be determined completely by its local behavior on a neighborhood of $x$. Consider for example $e^{-1/x^2}$. This vanishes on a sufficiently small neighborhood of $0$ so $[e^{-1/x^2}]_0 = [0]_0$, but of course $e^{-1/x^2}$ is not identically zero.

However, considering

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{F}(U) &\to \prod_{x \in U}\mathcal{F}_x \\ s &\mapsto \prod_{x \in U}[s]_x, \end{align*}\]we obtain an injective map. This means that knowing each germ $[f]_x$ lets us reconstruct the entire section $f$. Said differently, knowing the behavior of $f$ locally around the points $x \in U$ reconstructs $f$ completely on $U$.

What about those morphisms? Here is how we define them:

Again for the categorically inclined you may recognize this as a natural transformation.

Any morphism of sheaves $\varphi : \mathcal{F} \to \mathcal{G}$ over a topological space $X$ induces a morphism on stalks $\varphi_x: \mathcal{F}_x \to \mathcal{G}_x$ at each $x \in X$ by sending $(s,U) \longmapsto (\varphi_U(s),U)$.

We also have the notion of a kernel for morphisms of sheaves.

Unfortunately the presheaf image $U \longmapsto \operatorname{im}(\varphi_U : \mathcal{F}(U) \to \mathcal{G}(U))$ is not always a sheaf. We define $\operatorname{im}\varphi$ to be the sheaf associated (sheafification) to the presheaf image.

A morphism of sheaves $\varphi : \mathcal{F} \to \mathcal{G}$ is said to be injective if $\ker\varphi = 0$, and surjective if $\operatorname{im}\varphi = \mathcal{G}$.

- A morphism $\varphi : \mathcal{F} \to \mathcal{G}$ is injective if and only if the stalk map $\varphi_x : \mathcal{F}_x \to \mathcal{G}_x$ is injective for every $x$.

- A morphism $\varphi : \mathcal{F} \to \mathcal{G}$ is surjective if and only if the stalk map $\varphi_x : \mathcal{F}_x \to \mathcal{G}_x$ is surjective for every $x$.

It also happens to be that when $\varphi_x : \mathcal{F}_x \to \mathcal{G}_x$ is injective the map on sections $\varphi_U : \mathcal{F}(U) \to \mathcal{G}(U)$ is injective for every open set $U \subset X$. It’s easy to see that the case with surjectivity is not true. Take for example the sheaf of smooth function $C^\infty$ on $\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}$ and the sheaf $\Omega^1$ of $1$-forms. We have the exterior derivative $d : C^\infty \to \Omega^1$ which is surjective on stalks due to the Poincaré lemma, but for example $d\theta = \frac{-ydx + xdy}{x^2+y^2}$ is a closed, but not exact on $\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}$ i.e. the map $d : C^\infty(\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\}) \to \Omega^1(\Bbb R^2 \setminus \{0\})$ is not surjective.

In order to end this at a cliffhanger I’ll give you the following. A sequence of sheaves

\[\cdots \longrightarrow \mathcal{F}_{i-1} \xrightarrow{d_{i-1}} \mathcal{F}_i \xrightarrow{d_i} \mathcal{F}_{i+1} \longrightarrow \cdots\]on a topological space $X$ is called exact at $\mathcal{F_i}$ if $\operatorname{im}d_{i-1} = \ker d_i$. A sequence like this is called exact if it is exact at every $\mathcal{F}_i$. The above exercise shows that, the exactness of a sequence of sheaves on $X$ is equivalent to the exactness of the sequence of stalk maps at every point $p \in X$.

An exact sequence of sheaves the form

\[0 \longrightarrow \mathcal{F} \longrightarrow \mathcal{G} \longrightarrow \mathcal{H} \longrightarrow 0\]is called a short exact sequence. You might wonder what happens to the sequence when we consider sections. The following proposition summarizes this.

So a short exact sequence of sheaves implies the exactness of the sequence of sections

\[0 \longrightarrow \mathcal{F}(U) \longrightarrow \mathcal{G}(U) \longrightarrow \mathcal{H}(U)\]for every open set $U \subset X$, but $\mathcal{G}(U) \longrightarrow \mathcal{H}(U)$ need not be surjective and this is the beginning of what will result in sheaf cohomology which we will hopefully look at in the near future.

-

Notice that we have a notion of sections regarding vector bundles also. Turns out that the category $\textbf{Vect}_X$ of vector bundles over a topological space $X$ is equivalent to the full subcategory of locally free sheaves of $\textbf{Coh}(X)$. ↩

-

There is an isomorphism between de Rham cohomology and the sheaf cohomology of $ \underline{\Bbb R}$ which can be proven by considering the de Rham complex as an acyclic resolution of $\underline{\Bbb R}$ when viewed as a complex of sheaves. ↩